Amin Gulgee

spinning threads that interweave sculpture, performance and curation

Get to know notable Karachi-based artist Amin Gulgee in this edition of #SAIatHome.

A solo exhibition of Gulgee’s sculptures, installations and new media works- The Spider Speaketh In Tongues is on view at South Asia Institute until July 9, 2022.

Amin Gulgee’s praxis explores unlikely connections to uncover alternative narratives, resisting conceptual categorization. He attempts to dissolve the divisions not only between the many layers of South Asian spirituality but those of gender and sexuality. This non-dualistic approach manifests itself in the materiality of his metalwork and is reflected in the philosophy behind his performative and curatorial practices.

“…works by Amin Gulgee bewilder us by the variety of their expressions, by an apparent freedom in technique and design, by the range of pleasures they offer…”

“I was young in the ‘90s and all of my education in Art History at Yale had been Western, and I felt there was a real need for me to reclaim the sources of inspiration from my South Asian heritage. ”

You have said that you did not want to be an artist. Tell us what led you to follow your artistic path? How would you describe your art practice?

My father was an extremely respected Pakistani Modernist. Growing up, both of my parents were very liberal with me. The only thing they asked of me was, ‘Please don't be an artist’, and I told them not to worry, it would not happen. I saw how difficult the life of an artist was, and I had no interest in being one. My father was a working artist, and I really did not want a life like that. I wanted to stay far away from the arts.

After I left Karachi for school in the U.S., I thought I would never come back to Pakistan, and I was not going to be an artist; those were the two goals I set for myself. Like any good South Asian, I planned to study Economics at Yale. In my first year there, on the insistence of my friend Dominque Malaquais, I went to my first art history class, which was about the Baroque period. I absolutely loved the instructor, Judith Colton. She spoke of gardens, and this set me on the path to a second major in Art History. I wanted to do my thesis on Moghul Gardens and that was a bit of a challenge for me because, at that point, Yale did not have an Islamic Art History department. However, Dr. Oleg Grabar, who was a leading scholar of Islamic art at Harvard, agreed to be my secondary advisor. I did my thesis on the Shalimar Garden in Lahore and won the Conger B. Goodyear award from Yale’s Art History department for it.

You had no formal training in Sculpture. Tell us how you learned to work with metal.

Copper and bronze are very tactile. Texture is incredibly important for me. I think that through touching the material you connect to something else, something truly profound, that is even beyond seeing it. I once met Dr. Annemarie Schimmel, the German Orientalist and scholar, when she came over to visit my father. She asked, ‘Do you know begreifen? It is perhaps the most Sufi word in the German language. It means learning through touch.’

I picked up my skills of metalwork on the streets of Karachi. When John McCarry, my partner, and I first came to Karachi from New York, it was the early 1990s. My parents were not that enthusiastic about me being an artist and I had very little money. It was a crazy time in Karachi. The military dictatorship of General Zia-ul-Haq had just ended. Although Karachi was embroiled in turmoil, there was a creative explosion happening at the time. There were a lot of people returning to the country and everybody was trying to seek out and rediscover Karachi for their own. There was only one gallery in the city at that point. That was the Indus Gallery run by the iconic Ali Imam. I approached him several times for an exhibition, and he finally agreed to give me one. At that point in Karachi, sculpture was very rarely shown. I had no equipment to make works for the show. So, I would go to Jamshed Road, where men who did bodywork on cars would set up shop at night. I would use their equipment and expertise from midnight to four in the morning and that is how I learned to weld, to solder and to manipulate metal.

Amin Gulgee talks about his process in a behind the scenes tour of his studio, where no visitors are permitted!

Is there a message in your mixing of various religious traditions in your works? You mentioned you had a liberal upbringing, what led to your interest in Islamic calligraphy?

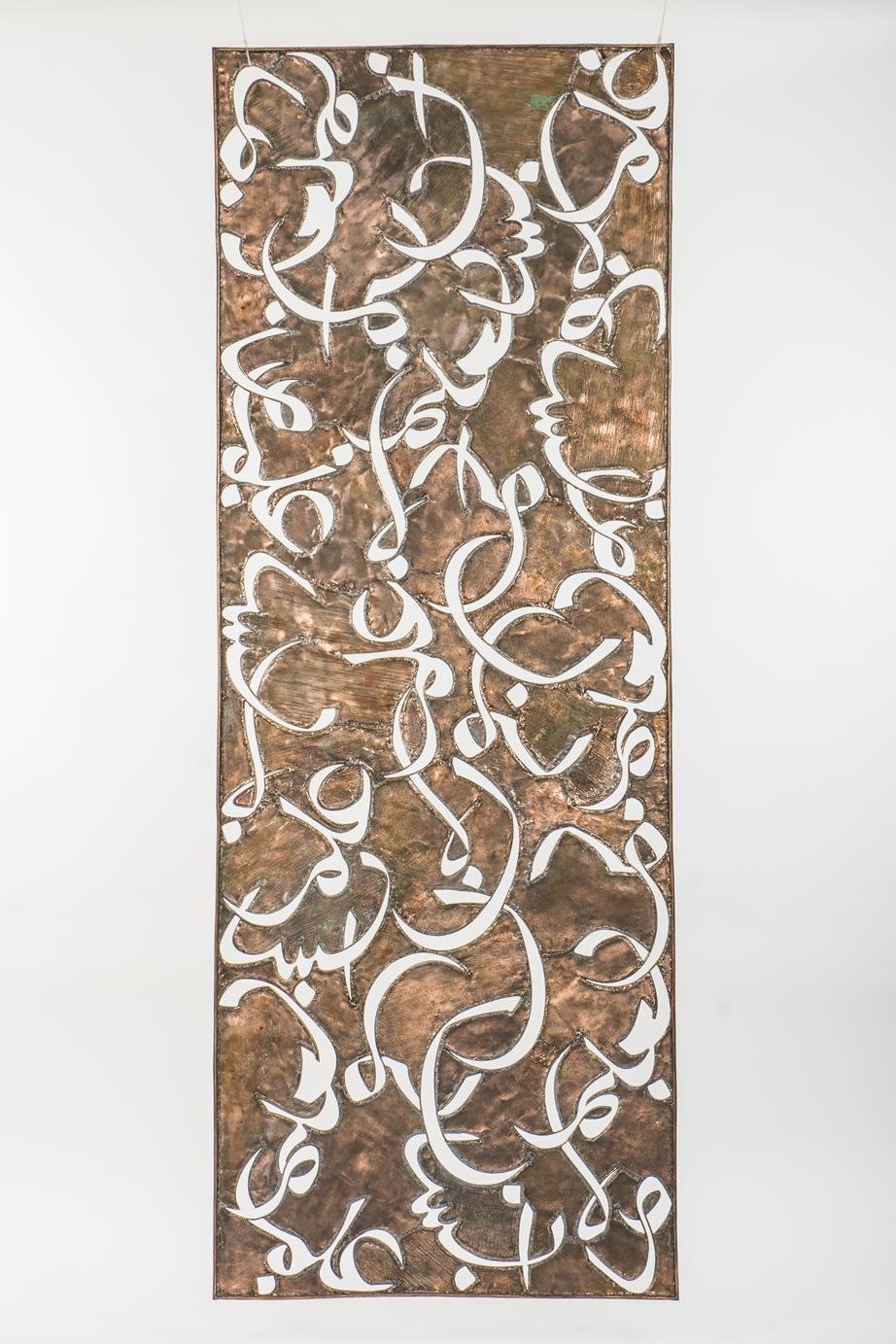

Contemporary artists were not engaged with Islamic calligraphy when I began my career. It was associated with the military dictatorship of General Zia-Ul-Haq and oppression. Muslims have created incredible objects in the past and I wanted to look back at these sources, and examine their philosophical basis. I was young in the ‘90s and all of my education in art history at Yale had been Western, and I felt there was a real need for me to reclaim the sources of inspiration from my South Asian heritage. My early work not only dealt with calligraphy, it also dealt with appropriating images of Buddha and Krishna, and all of the objects I had grown up with in my parents’ house.

There is a particular line from The Quran that you have used repeatedly in your works, and that has morphed over the years. Can you explain your choice of this phrase?

My father was a great calligrapher and he could write in all the major Arabic scripts. I don’t think of myself as a calligrapher. I am an object maker. I am interested in form. I want to go beyond the content of the line: to play with form, emotion and energy.

I have only used two lines and one phrase in my sculptures. One of them is from the Iqra, and that is the line you will find in the works that I am bringing to Chicago. It says, ‘God taught humanity what they knew not’. The line can no longer be read as it is deconstructed, which, for me, personalizes it. These becomes my private love letters to the Divine.

I have also used the phrase ‘Alhamdulillah’ in the Square Kufic script as the basis for my geometric forms, as you can see in my latest work, Nonbinary Cube.

Can you explain the reference to the spider in your exhibition at SAI? What does it symbolize?

I love spiders! When I saw Louise Bourgeois’ work, it was one of those moments where you just feel so happy to be alive. I absolutely loved the work and I wanted to create my own spiders. There is a tradition of using anthropomorphic forms in Islam. I used the Islamic script again, using every letter of the line. You cannot, however, read the text in my sculptural spiders. These arachnids are balanced on three points, and dance into the air. I feel like my entire trajectory is picking up different threads of a web, and seeing where they lead me.

Talk to us about the performance component of this exhibition-

Entitled Kiss of the Spider Woman, was a 77-minute collaborative performance. I love cross-disciplinary interactions and I will be working with a whole variety of people. I want this to be experiential and visceral. The idea is for the audience to move through the space, amid the sculptures and the performances. The way I approach performance is the way I approach my sculpture. It is an act of letting go.

Kiss of the Spider Woman took place at SAI on Sat, April 9th. Follow us on our social media to view highlights from the performance!

How do you relate your sculptures to your performances and how does it inform your overall practice? Can you give us a background on your performances and how they are conceived?

In my practice, I feel the need to physically activate objects that I have created, blurring the line between my sculpture, installation and performance. Performance is ephemeral and it becomes a medium to express ideas that challenge and question societal norms. In the context of Pakistan, performance is new, which allows many ideas to be publicly explored and digested.

My performance trajectory began with my engagement with Karachi's fashion scene. During the restrictive dictatorship of General Zia-ul-Haq, fashion shows were not encouraged due to his policy of Islamization. In the early 1990s, fashion exploded and was extremely experimental. There was also a great dialogue with the visual arts. Female models strutted bravely down the catwalk creating larger-than-life, theatrical personas. Initially, I included my gold-plated copper jewelry onto various designers’ clothes.

In 1999, I got the opportunity to conceive and present a show of my own which I titled Alchemy. Having worked closely with the country’s top models over the years, I was extremely familiar with the way they moved. I created large, metal objects for each of these women that they could wear and walk on the catwalk. Alchemy was divided into three acts: Bronze, Silver and Gold. Each part was introduced by a performance work. Before the first section, I covered my body in clay and clamped a bronze self-portrait mask weighing three kilos onto my head and danced to a morning raga. I can still remember the weight of the headgear and hearing myself breathe beneath it. It was a transportive experience.

In 2004, a year after the U.S. invasion of Iraq, I stepped away from the catwalk format and enacted Calculate which was performed at Canvas Gallery in Karachi. Seema Nusrat, who had just graduated from art school, calculated with a large abacus strung with colonial-era dolls’ heads. This began a continuing series of around thirty performance works to date. In 2013, I performed Love Marriage in the open-air courtyard at the Indus Valley School of Art and Architecture in Karachi. Artist Saba Iqbal and I wore geisha-like makeup blurring the lines between masculine and feminine. I devised a wedding ceremony consisting of breaking eggs into each other’s palms, wearing objects I had created. In 2014, in the theater of the Arts Council of Karachi, I staged Where is the Apple, Joshinder?, working with eight musicians, dancers, artists and actors over a period of seven months to choreograph and envision the performance, which took place within my installation Char Bagh. This performance examined gender roles and dynamics.

In 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic, I created a performance solely for documentation in video and photography. In Healing II, I had my head ritualistically shaved, while wearing metal wings, within my rooftop installation Salaam Gaudi, surrounded by people close to me. This was a continuation of an earlier performative work of mine, The Healing, which took place in 2010. Both works dealt with death and resurrection. In 2021, I conducted a performance at the gallery of the Cité internationale des Arts in Paris. Entitled This Is Not Your El Dorado, this collaborative performance was comprised of 18 participants including myself. It was part of Performative Utopias, a weekend-long academic conference on contemporary African performance that was organized by art historians Dominique Malaquais and Julie Peghini.

You also have a two decade long curatorial practice, what can you tell us about these projects?

I began my curatorial practice in the late 1990s with Urban Voices, which took place in the main lobby of the former Sheraton Hotel, during ArtFest Karachi. This series of exhibitions had four iterations, and included emerging Pakistani artists as well as established ones. In 2000, John McCarry and I established the Amin Gulgee Gallery, an artist-led, non-commercial space. We live upstairs. This was conceived as an experimental space to incubate new ideas and foster artistic dialogue in Karachi. Every exhibition is accompanied by a catalogue. We have hosted over thirteen exhibitions.

One was The 70s: Pakistan’s Radioactive Decade, which took place in 2016. It was an attempt to understand this tumultuous decade of Pakistan’s history through the prism of cultural production, and included the work of fifty-one artists. It was accompanied by a book, published by Oxford University Press.

In 2017, I was the Chief Curator of the inaugural Karachi Biennale, Pakistan’s first biennial. The Karachi Biennale 2017 contained the work of 182 Pakistani and international artists, in 12 venues across the metropolis. The thematic was ‘Witness’. I continue to venture outside conventional art spaces, having curated six other public art events. In these shows, there is usually an emphasis on performance and new media

“The Biennale, was the first of its kind. It utilised public places for the display of contemporary art, which in turn made it available for the masses, instead of being restricted to gallery viewing.”

You have numerous public sculptures displayed in Pakistan. You also have a sculpture at the United Nations in New York. Can you comment on this?

Commissioned work scares me. Even in the beginning of my career as an artist, I always thought that I would much rather make a small pendant, over which I had complete control, rather than a monumental sculpture dictated to me by a client. My first commission was in the mid-90s for IBM, which was opening an office in Karachi. They wanted a work reflecting the future of technology. The company gave me access to their warehouses in which discarded computers were stored; I ravaged them. In order for me to understand this new material I smashed these machines, and, from their entrails, I excavated motherboards. These captivated me. The grid of these boards reminded me of the Square Kufic script that I had been using. I ended up creating a nine feet high work in the shape of a DNA molecule. The work was entitled The Neuron Chip.

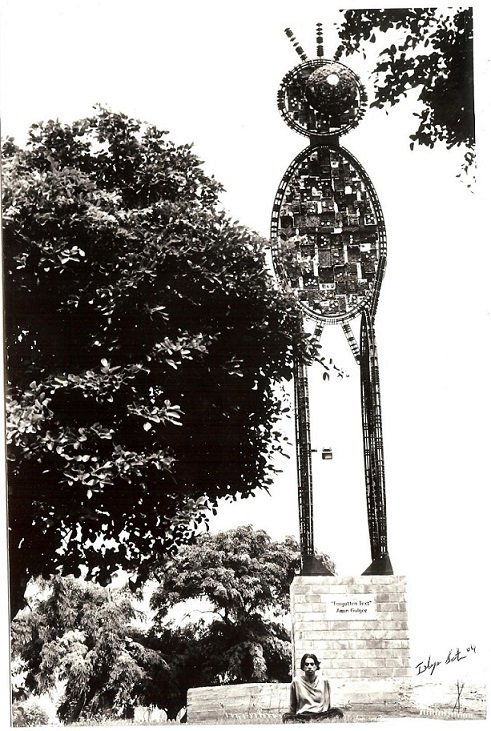

In 2002, I was asked by a group of national and multinational companies to propose a public sculpture which would be placed upon Bilawal Roundabout in Karachi. Since I don’t sketch my objects before making them, I proceeded to make several models. Being interested in text, I used hieroglyphics from Mohen-jo-daro, a city of the Indus Valley Civilization, which flourished in modern-day Pakistan in the Bronze Age around 3300-1300 BCE. The sculpture I put forward was supposed to be twenty-feet high, but I increased its scale to forty-feet. I embraced the chance to create a public work for my hometown.

The form of Forgotten Text was constituted of three Indus Valley hieroglyphics. Their ancient writing system has yet to be deciphered. The body of the object was covered with computer motherboards worked upon with copper wire and embellished with round mirrors, which often appear on traditional Sindhi clothing. The grid of the motherboards was like an aerial view of my city: ordered yet chaotic. I wanted Forgotten Text to echo a charioteer, referencing the roundabout as a starting point for donkey cart races. On weekends, these donkey chariots would fly across the streets of Karachi navigating through traffic. The donkey, for me, represented my metropolis, which had seen years of bloodshed and violence. It was an animal that was overworked, stubborn and yet incredibly resilient.

After its placement I was thrilled that the city appropriated it. It was covered in flags for the birthday of our female Prime Minister, Benazir Bhutto. For the Prophet’s birthday (PBUH), it was illuminated with green lights. However, in January 2008, a few months after the murder of my parents, I was heartbroken to see that overnight it had been removed in its entirety.

My public sculptures at Parliament House in Islamabad and at the United Nations in New York were not commissioned. They were obtained and installed after I had made them for myself. There is a challenge in scale. As soon as I could afford it - copper and bronze being an expensive medium - I started increasing the proportions of my work. Since most of my work is assemblage and not done in a single casting, there are structural and aesthetic concerns that arise when enlarging it. Usually when a series begins it is relatively small. When I am more comfortable with the form, I start gradually increasing the size of the work to better understand it. There is also a difference in how one approaches and registers a monumental object versus one that stands upon a plinth.

We are very excited about Spider Speaketh In Tongues- the exhibition that you and Adam Fahy-Majeed are bringing to Chicago. What can we expect from your upcoming exhibition at South Asia Institute?

It is such a privilege and an honor to come to your space and show my work in the United States. The Spider Speaketh in Tongues will be an immersive experience interweaving sculpture, installation, new media and performance.

However, there is one thing I would like to say, something truly important to me. Although it’s extremely exciting to bring my work here, I simultaneously believe that it is very important to make change in one’s context. My context is Pakistan, and I believe that art can bring about change there. I think it can open eyes and hearts to many things and address challenging issues.

Here at South Asia Institute our mission is to build bridges, not only within our own South Asian communities, but also with the general community at large. And so we welcome Amin to Chicago and to our space.

All images and videos courtesy of the Artist and Amin Gulgee Gallery