Ruby Chishti

Ruby Chisti with Sketch of a Fading Memory detail

Ruby Chishti (b. 1963 in Jhang. Pakistan) is an installation artist who graduated from the National College of Arts, Lahore, Pakistan and currently lives and works in Brooklyn, New York. Using unconventional mediums, her artworks are sculptures that talk about fragility of human existence, migration, Islamic myths, gender politics, memory, universal theme of love, loss and of being human. Her installations, sculptures, and site-specific works have been exhibited at Asia Society Museum NY, Queens Museum, Rossi & Rossi Hong Kong, Aicon Gallery (London & New York), Vadehra Art Gallery, New Delhi, India, Arco Madrid, Art Hong Kong, India Art fair and The Armory Show NYC to name a few.

“My engagement with the material world of “waste” is intimate, sensorial and profound. Inspired by socio-political narratives of exile, dislocation, trauma, destruction, I transformdiscarded mass produced, clothing and hand-sew thousands of layers of folded scraps of fabrics into audio-visual installations, as they silently preserve the physical and emotional spaces held by their prior owners yet haunted by their absence.”

Can you tell us about your art practice

Art making has been an absolute necessity for me. Failed experiments, limitations of material and challenges push you into unfamiliar zones, leaving you vulnerable and that is exactly where you find possibilities to grow. My recent work provides an urgent template for conversation with the passage, persistence and survival of time and people's relationship to places.

My lifelong fascination with the tenacious and fragile nature of our own existence has inspired me to reinvent sculptural forms through a variety of materials that forge an intrinsic impression of the collective human experience.

I select my materials carefully and treat them as if they were humans who could feel and heal if employed with care. The creative process begins with seeking out intriguing articles of clothing, frequently at thrift stores in my Brooklyn neighborhood or wherever I go in the world. I buy pieces such as altered ceremonial garb, or color-faded jeans or taking fragments of clothing and disassembling it as in natural systems, waste may become "food" for new cycles of growth; life can be infinite and cloth can be immortal.

What led you to become a sculptor?

Art served as an emotional and intellectual outlet, distracting me and serving as the platform through which I found the safety to grow. I chose sculpture because of its physical nature and the challenges that come with it for a full engagement and most of all the tactility of materials fascinate me.

As the fourth daughter born in a patriarchal society where female lives are deemed culturally subordinate; my earliest childhood memories are that of gender discrimination and a strong sense of feeling unwanted. I found solace in the quiet moments of crafting my own dolls out of scraps of cloth and toys using mud. As early as eight years old, I was transforming my sibling's discarded/out of fashion clothing into the recycled pieces I could wear; as I was not into wearing any generic clothing that was given to me. In retrospect, I recognize that I have always had immense appreciation for the transformation of discarded materials.

I trained as a sculptor in western classical manner at National College of Arts Lahore, Pakistan, using only clay, plaster, wood, metal and it was not until 1999 when I established a connection between heaps of cast offs that I had collected over the years and a human life: my mother, bedridden after an accident. My work demonstrates an approach to utilizing waste in a highly visible way, reflecting that discarded and abandoned things hold the power to provoke a feeling in the viewer of tenderness as these unwanted objects become a metaphor for life's transience. Through its materiality and close relationship to the body, clothing develops history and biography and continues to have a "life" even after having been discarded.

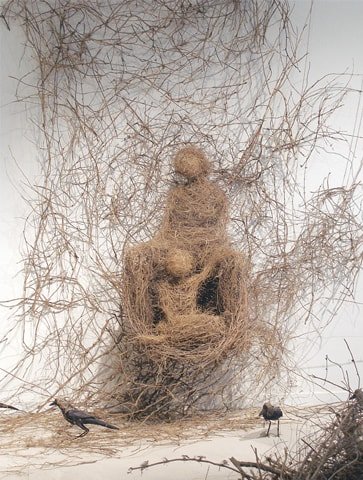

Sketch of a Fading Memory II Fallen twigs, thread, glue. Over life size.

Sculpture offers space to grow due to its unique challenges and allows opportunities to experiment with different materials like fallen twigs, recycled cloth, stitching, stuffing, and to explore through unconventional ways such as casting fabric in molds, fabric manipulation, layering and so on. Sometimes the limitations of a certain material and my desire to mold it in a certain way creates a dialogue that there could be no substitute for. Just one material can offer thousands of possibilities. I also find it surprising what your hands can do in the process of creating that you had not envisioned before. To touch, hold, walk around, repair, rebuilding are all perhaps ways to understand the world around me.

“My installations with fallen twigs created in the past, were ephemeral and fragmented similar to the nature of our memory. I let the viewers experience the works as true and close to my own experiences. I would rather use the natural materials and let them live as long as they can and not sacrifice the material for the sake of permanence. ”

You prefer to use organic material that derives from nature and has an ephemeral quality in your works that may eventually perish. How do you feel about the digital archival of art that allows works to live on in different media and forms?

I hardly consider anything as "permanent" and what is considered permanent is also questionable, but "transformation" is perpetual. Historically bronzes have been melted down to create weapons of war or to create new sculptures commemorating the victors. Far more stone and ceramic works survived through the centuries, even if only in fragments. The 6000 year old textile that can survive in my work of recycled fabric (combination of organic and synthetic fibers) is not so perishable, some of my other works created in fallen twigs were intentionally meant not to last. However, the world we live in now is far more dangerous and vulnerable than ever before with increasing climate crises, wild fires, hurricanes, floods, deadly viruses, hostility and terrorism. These are far greater issues than focusing on physically preserving works of Art.

I believe art is the most powerful way to connect and communicate with the world but artists cannot merely rely on the limited opportunities offered by Museums to showcase their works. Museums are few in number in comparison to the amount of art produced and they are less inclusive towards artists of color who might never align with their views and philosophy. We are very fortunate to live in an age of technological advancement where shared knowledge is almost free and we can rely on digital archives. Digital archiving bridges this gap and plays a crucial role in making artworks more accessible to the viewers and preserving historical material for generations to come.

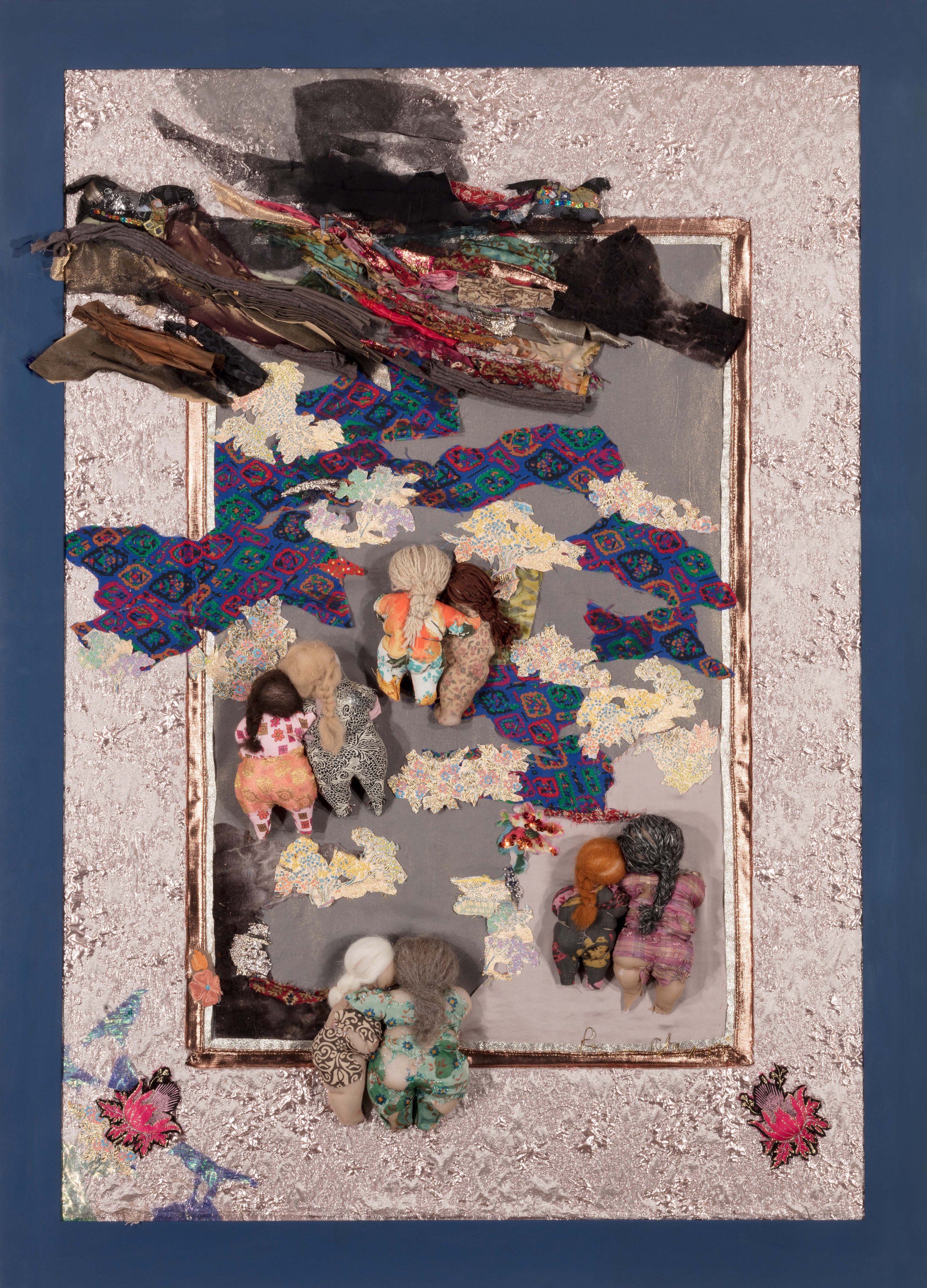

The Present is a Ruin Without the People

“In ‘The Present is a Ruin Without the People’ layers of diversely-sourced fabric scraps set the anatomical stage. The visual portion of this installation symbolizes the physical and emotional spaces that are unwillingly abandoned by communities seeking shelter, yet remain haunted by their absence.”

Free Hugs Fabric, polyester, yarn, thread, steel and wood. 11 pairs H 71cm approx.

Your works display an array of women centric technical skills such as knitting and weaving. How does this speak to the generational connection between women, which stands the test of time and reflects the resilient nature of womanhood?

Textile techniques of weaving, stitching, sewing span global cultures. For centuries women's contribution has been downplayed, with sewing dismissed as domestic labor. But when we lift the curtain on the role of sewing in history, it sheds light on the ingenious women who have long used textiles as a tool of empowerment and a way to speak when nobody will listen. Back in 1830, 17-year-old domestic servant Elizabeth Parker used needlepoint to document her incredible life and recount her harrowing experience of surviving sexual abuse. Women of the Black Panther Party used their all-black ensembles as a symbol of unity and resistance, and in the 1970s Argentina, Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo embroidered white headscarves with the names of their missing sons and daughters and wore them in an act of silent protest against the military rulers. The Suffragette banners so much a part of the feminine struggle and embroidered with names of imprisoned women, drew on women's traditional skills in needlework. More recently Pussy hat co-creator Jayna Zweiman, who learned to knit while in architecture school, returned to it while recovering from an injury and resorted to it to express strength of feeling against political powers

“Art making has been a necessity for me to bring into focus gender disparities, patriarchy and exclusion. Molded by my personal background, and continuously awakened by the state of current affairs, I am compelled to create works using these basic yet powerful tools that strive to provide a safe space for us to endure in day to day life. ”

The inspiration for your works derives from your childhood experiences and memories? Can you tell us the inspiration behind the dolls in "The Only Blindspot in History II" and what they represent for you?

Although I had the history of making my own dolls as a child, I never incorporated cloth into my art practice before. The personal iconography evolved during the time as a caregiver for my mother for over a decade in Pakistan. Those countless moments of caring, performing transfer, lifting her to sit; each process was repeated for years and retained in my mind and hands so well that I could recreate her in any material effortlessly.

I began to feel a connection between these castoffs and a gradually deteriorating physic of my mother and the thoughts of losing her and fears of my own.... I started stitching and stuffing these forms sitting by her bedside while she would sleep. These are ancestral figures, women that I have always seen around me whether walking on the streets, seated on the back of motorbikes, or mourning at the birth of yet another girl child. My reference here is to one of the earliest works from1999. I had made a comforter for my family out of old clothing titled" My birth will take place a thousand times, no matter how you celebrate it" This particular work was a direct reference to my childhood memories of lived experiences of gender disparities.

The Only Blind Spot in History images by Jonathan Castillo

“In “The Only Blind Spot in History” refigured garments embody the touch of proximity and togetherness appear on a missing page from history. By incorporating my own personal iconography the profusion of these miniaturized forms solicits something of the creativity meant to last. These female figures are rendered with scraps of their own ceremonial clothing, sometimes tied with thread or sewn together, celebrating their existence. ”

Images courtesy of the artist and Hundal Collection