Chitra Ganesh

In her drawing-based practice, Chitra Ganesh brings to light narrative representations of femininity, sexuality, and power that are typically absent from canons of literature and art. Her wall installations, comics, charcoal drawings, and mixed-media works often take historical and mythic texts as inspiration and points of departure to complicate received ideas of iconic female forms. Her vocabulary pulls from surrealism, expressionism, Hindu and Buddhist iconography, and traditional South Asian pictorial forms, connecting these sources with contemporary mass-mediated visual languages.

DIGITAL ANIMATIONS

The images of the digital animations below were originally commissioned for the Rubin Museum of Art’s exhibition Chitra Ganesh: The Scorpion Gesture, curated by Beth Citron. They were presented later at Times Square's Midnight Moment and at The Kochi Muzuris Bienniale 2018. The animations were available for public streaming for the first time, exclusively through South Asia Institute from January 9-31, 2021.

Developed and Animated by the STUDIO NYC

Silhouette in the Graveyard

Rainbow Body

Adventures of the White Beryl

Metropolis

The Messenger

a conversation between Chitra Ganesh and Dr. Natasha Bissonauth on Chitra's work, representation, narratives and agency

Originally recorded on January 16, 2021. Forward written by Dr. Natasha Bissonauth.

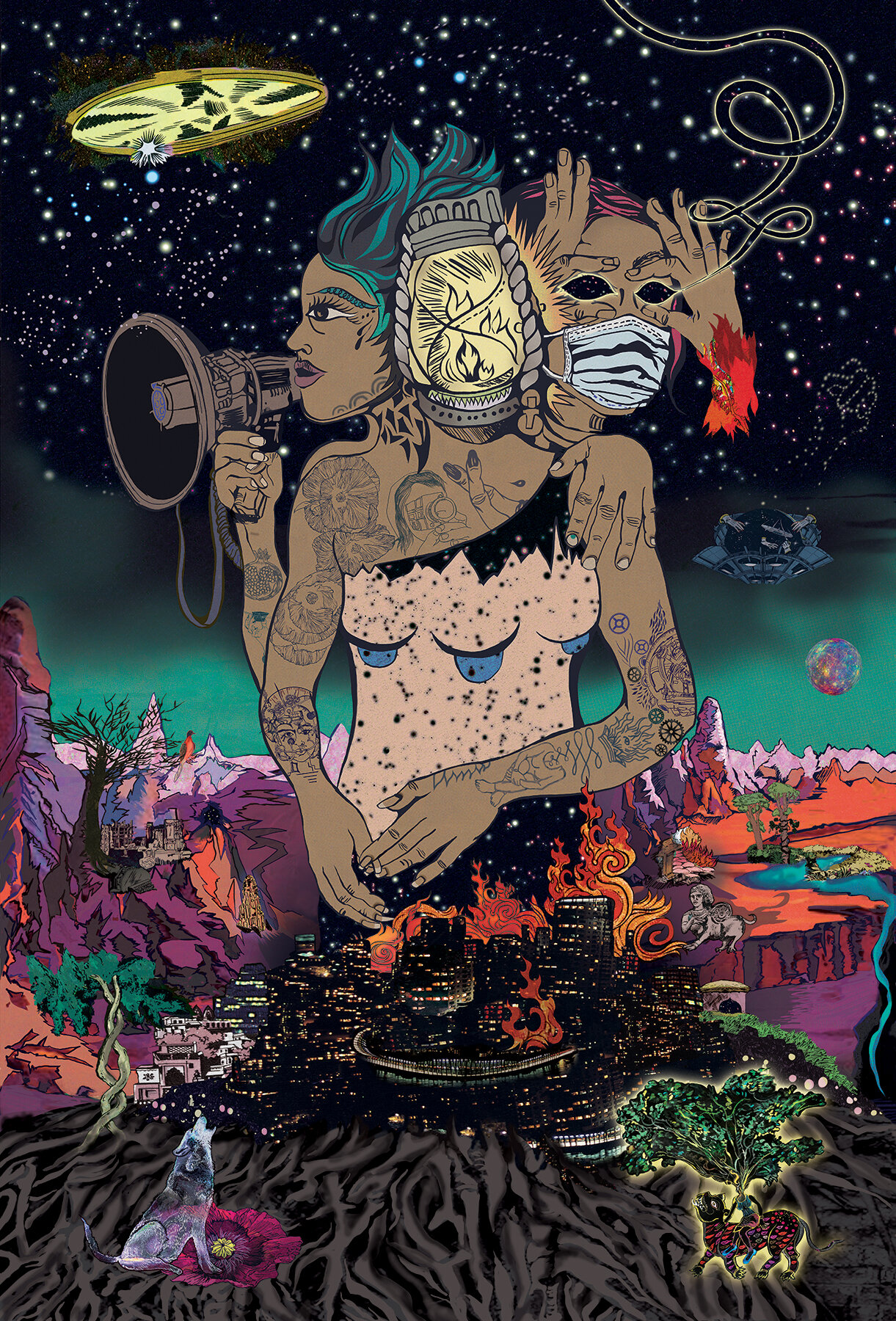

Brooklyn-based artist Chitra Ganesh (b. 1975) was born and raised in New York City. For the past twenty years, she has developed an iconic graphic line animating a set of speculative characters in complexly fantastical settings that urgently transport the viewer from the here and now. Working across various media, her drawings on paper, murals, print media, and digital animations, draws on traditions of comics, mythological and science fictional representations, while also plumbing Bollywood aesthetics, surrealist writing, and expressionist style to imagine and give form to the not-yet. Often working in series, she ultimately engenders her own pantheon of deities, archetypes, and iconographies that spiral through her own forms of storytelling and narrative logic. Always queer, feminist, brown, and anti-imperialist, her fierce femmes may very well guide us through these apocalyptic times toward a more just and collective sense of being-with.

Ganesh has a B.A. in Art Semiotics from Brown University and an MFA from Columbia University (2002). With transnational gallery representation, she has exhibited widely, in innumerable group shows in the US, Europe, and Asia. She has had select solo shows at MoMA PS1, the Andy Warhol Museum, the Brooklyn Museum, the Rubin Museum of Art. Currently, she has a solo exhibition at the Leslie Lohman of Art, titled, A City Will Share Her Secrets If You Know How To Ask (2020). She's part of some prominent public collections, including MoMA, the Smithsonian, PAFA, Baltimore Museum of Art, the Saatchi Collection, Burger Collection, and Devi Foundation just to name a few.

In this conversation, we discuss the politics of Ganesh’s aesthetic form during times of collective crises, the irreverence of play in the archive, the dissent of the speculative, time-travel, and diasporic accountability.

Natasha Bissonauth (NB): Let us start with the works up on SAI’s website. Can you briefly introduce these digital animations which has, consequently, provided an occasion to gather?

Chitra Ganesh (CG): Hi everyone and thank you! I am really looking forward to this conversation and I couldn’t agree more with needing structures for our voices and ideas that have often through the cracks of mainstream culture and discourse – thanks SAI for providing this online platform.

The Scorpion Gesture (2018) is a suite of five short animations curated by Beth Citron and commissioned by the Rubin Museum of Art around the theme of Futures. Padmasambhava, who’s known as the second Buddha and who is credited with bringing Buddhism to Tibet, functions as the work’s point of departure. In my research, I found that the figure of Padmasambhava was key to imagining futures in part because his legacy is speculative – foretold to come every two hundred years in the form of termas or buried treasure that people find all over the place. As moments in his world collided with challenges of our 21st century, I was inspired to make these works.

NB: The works function like a portal between worlds, then and now, and along certain political axes. In many ways, you mark end times as a recurring event, which we see in myth and science fiction but also in the very real material conditions of many indigenous, black, and brown lived experiences. This kind of time-travel makes me think of the movement of temporality present in your work. As an incisive lens on temporality, your aesthetic implodes linear, straight heteronormative, and colonial notions of time, engendering instead a concept of time, in your words, as a spiral. And when you’ve said spiral, I’ve imagined a cyclic motion or centrifugal force accompanying the spiral. How does movement enact these ideas of time, of queer time?

CG: Yes, I’ve definitely been invested in thinking about time differently and understanding movement through time in much of my work. The formal aspects of animation made this project really exciting. In animation, you experience dimensionality such as depth and space, but inside a fantastical world. And camera motion in animation – whether scrolling up or pushing in enhances how one would visualize the collapsing or rejoining of different time periods. As for spiral time, there’s a lot of evidence of folks thinking differently about time, that is, moving beyond the notion of time as an arrow of linear progress – with parts that are considered inevitably ‘backwards’ and ‘forwards’ on the timeline. I think of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and the arc of the moral universe that bends towards justice; or Ocean Vuong’s On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous who connects how time’s spiral movement with why we might find ourselves returning to the same suffering over and over again. I personally started thinking about time as a spiral through grief, which is also a spiral – where you can find yourself in a different moment in the grieving process that feels similar, yet distinct from something that already happened. A circular idea of time aligns with both trauma and justice. And overall, another approach to history that moves towards a more just future offers a different way of seeing where we are. These animations speak to all this, but in particular to the trauma and justice of our time and in times past. The white barrel in Adventures of the White Barrel (2018) is a huge cosmological manuscript compiled in the mid to late 17th century and first rediscovered in the late 1980s, hundreds of years after it was made. It took a team of scholars years to decode the work, which was situated somewhere between Chinese astrology, Buddhism, and numerology. As I was making my work in 2017, I connected this to astrology, Tarot, and other contemporary ways of divination that I see re-emerging during our precarious times. Another gateway for thinking of time as spiral is of course my longstanding interest in myth, more specifically how mythic structures often elude linear time. Whether Star Wars or The Odyssey, time starts in the middle. For these works, I wanted a dreamlike quality and interior space where everything is potent, compressed, and moving across many temporal and spatial dimensions.

NB: We are definitely spiraling through multiple and simultaneous pandemics as it were. And, of course, in times of collective crises, there’s always been a role for the artist. There’s always been a role for art. I am curious, how does an aesthetic ethos emerge for you?

CG: I’ve been moved by the aesthetic of protest in recent years and especially in 2020, where the message and the medium come together in an urgent and DIY way. Here, I am thinking not only of scenes of bodies in protest but also the makeshift quality of cardboard signs (most likely made on the back of a detergent box with a marker) that people carry in their pockets or behind bikes. I also think of the evolution of public art. In years prior, we’ve seen the destruction of public art, such as the 5Pointz building in Queens, which for decades was a major site for graffiti. But public art is also flourishing anew in a sense during these times. When I was working on my solo at Leslie Lohman, located in Soho in lower Manhattan, I noticed something exciting around the corner. The neighborhood had evolved into a high-end shopping area full of tourists for years, but during these particular times, corporations have boarded up their storefronts because it’s cheaper to remain closed than serve people. I saw four people with two ladders making their own installation on three boarded up windows next to mine. Given how much we have to be in public space now, as a sign of our times, I think these public gestures are a big deal, and vital. My recent work has definitely been inspired by much of 2020 – the problems but also aesthetic ethos and the hope needed for moving out of this moment.

NB: Public display as a response to aesthetic ethos is compelling and I’d like to return to this. We find ourselves in need of a radical reorientation, given the global rise of nationalism and fascism. For our purposes, we can single out Modi's India in this instance. But your attentive eye toward collectivity and coalition across aesthetic traditions and borders provides an antidote of sorts. What lessons might the diaspora hold on to here when looking at your work?

CG: The diaspora, that term itself and its resonance, is much changed over the last three decades. Whether or not one chooses to be invested in this category, it remains fluid, invoking very different regions, nationalities, and patterns of migration. ‘Diaspora’ is like any social formation in that it can willfully or unconsciously replicate existing power hierarchies. Within our communities, this includes caste, skin color, region, education, sexuality, gender norms, just to name a few. One can either reproduce those power structures in daily behavior or think about new ways to be by deepening our understanding. Growing up, there was a lot of attention to racial and economic equality in my household, but there was a relative absence of discussion around gender norms and caste. Everybody inherits gaps and prejudices, which manifests differently if your parents grew up upper caste but working class, if your parents grew up during partition, etc. – and there’s endless examples like that. I would like to take what resonates, but ultimately shed light on broader understandings of power and possibility. The work of unthinking that I’m still doing, I believe is part of our life’s work.

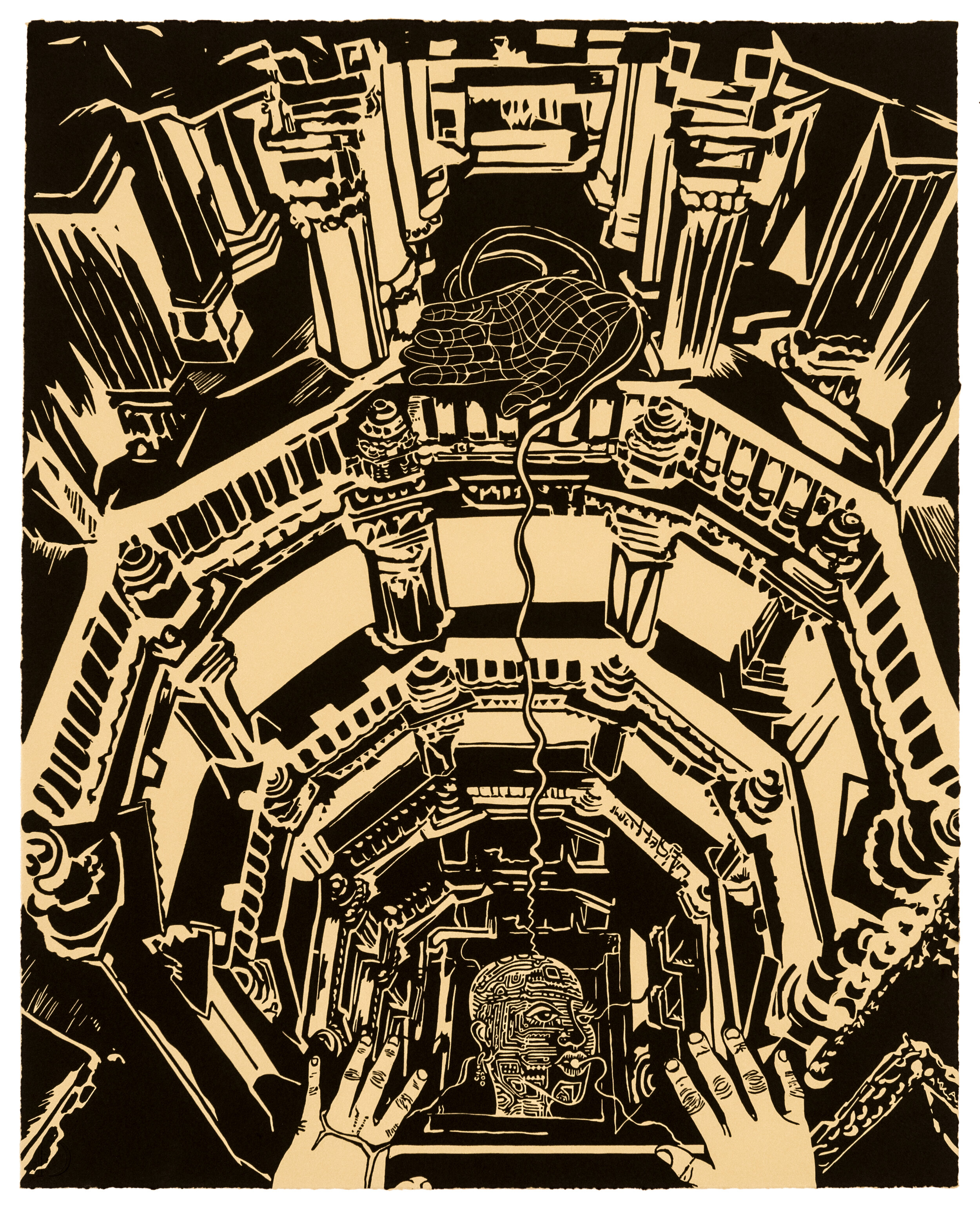

NB: Thanks for this careful response. How you name diaspora’s accountability without annexing the aspirational as a task mode feels like a crucial framework for analyzing brown art. I wanted to ask a more specific question about your aesthetic influences. You’ve mentioned in the past how woodcut informs some of your imagery. Here, I am thinking of Sultana’s Dream (2018), and how woodcut as a form influences your speculative aesthetic.

CG: Sultana’s Dream is a suite of prints, which takes as its point of departure a 1905 feminist science fiction novella with the same title by feminist, educator, and social reformer Begum Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain, known as Begum Rokeya. At the beginning of the story, the main character, Sultana, is lazing in her bedroom contemplating the condition of Indian womanhood. She accepts an invitation from a friend she sees her at the window, and takes a journey to this other place called Ladyland. Hossain writes a feminist utopia that offers a different template of the future. Interestingly though, the writing does not necessarily describe a feminist utopia as such but shows one through visual detail. For me, I found there to be various points of confluence between the story and the formal (and political) aspects of woodcut, which in this instance, is relief printing using linoleum; the image is carved in reverse on a linoleum block, and then printed on paper. I interpret particular aspects of the story that lend themselves to the formal qualities of graphic balance. For example, in the story Sultana is with her guide and friend sister Sarah, who explains how in Ladyland there is ample time for both industry and dreaming. The inhabitants all work efficiently, leaving the remainder of their time for experimentation and free thought. Thinking through the graphic balance of black and white, and developing a sense of harmony between foreground and background – allows me to visualize subjects in balance with their worlds, surrounded by and inextricably linked to the environment. I’ve noticed this same attention to graphic equilibrium also appears in political posters and graphics. There is indeed a lineage we can trace between woodcut and contemporary poster art. The author also describes in detail Ladyland’s open border policy for refugees, connecting to the ‘Refugees are welcome here’ posters I would pass in my neighborhood 2018 onwards. Hossain also writes about harnessing water, storing, and distributing it and part of what I love about this form, about print culture in general, is its reproducibility and accessibility. Ladyland’s environmental, scientific, and justice-oriented focus occur at multiple levels. Finally, woodcuts have historically taken up cities and their structures. Another point of inspiration like this is a suite of woodcuts called, The City (1925), by Frans Masereel a Flemish artist, printmaker, and painter making me think of echoes between 1920 and 2020. During our last pandemic and the racial riots that ensued, the way that the flu spread through soldiers to Asia, colonialism…there’s a lot to unpack there. But ultimately, the idea of people in relation, in relation to structures in the world feels formally embodied by woodcut and relief printing.

NB: In a question about form, the spiral inevitably recurs as an organizing principle. Well, you’ve said so much already. I’d like to continue discussing the speculative in your work, in particular, its dimensions of play. As you know, I work on play as an aesthetics of dissent in queer of color art. Certainly, there’s an immersive element to your work, and your interest in myth and science fiction, interpreted through the comic book line, suspends from the here and now, while simultaneously gesturing toward transforming it. Like other aesthetics of play I’m invested in writing more about, such as camp, parody, or the carnivalesque, there’s an element of irreverence and subversion embedded in your speculative lens. Can you elaborate on how the speculative upends normative power structures?

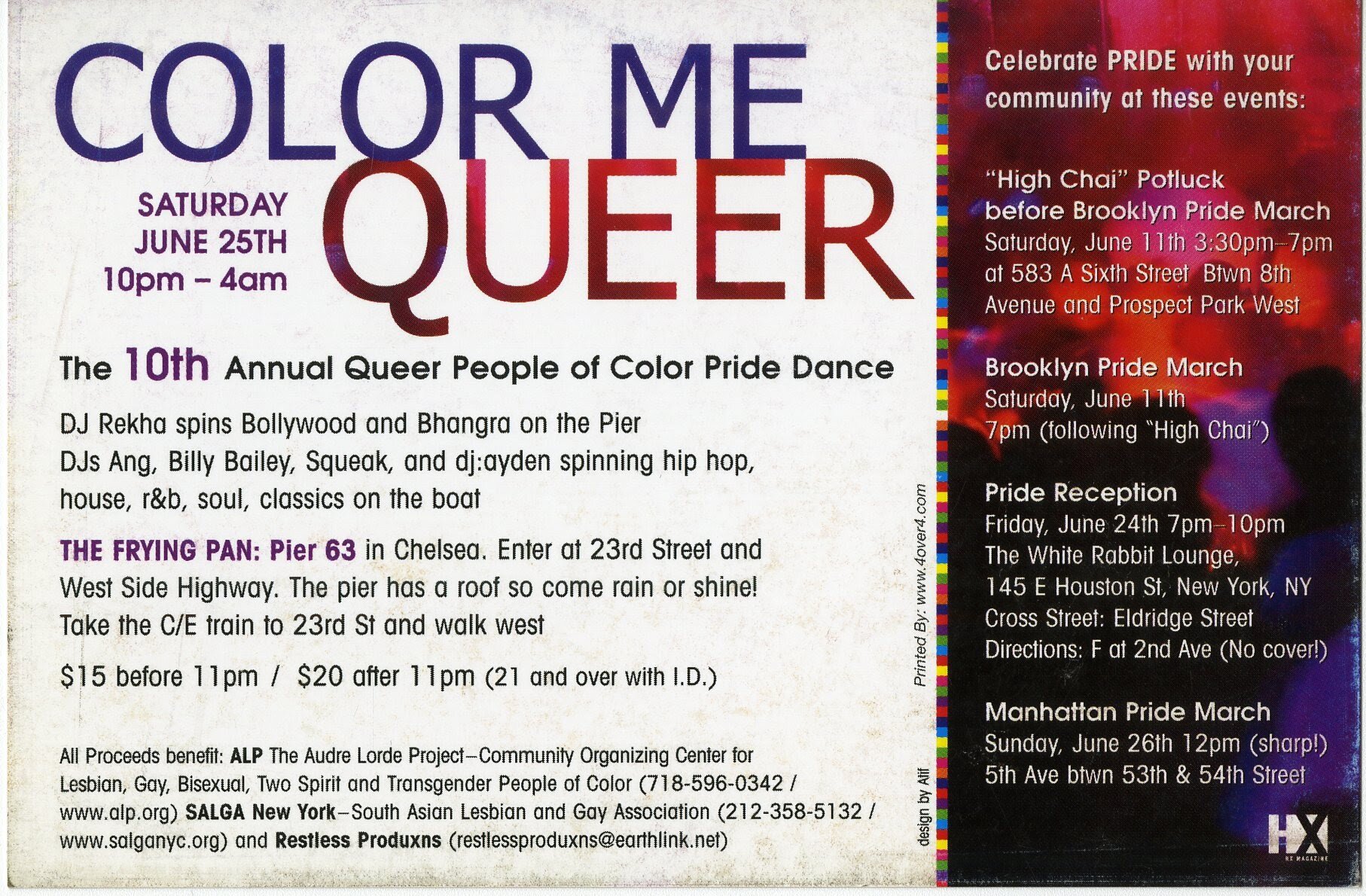

CG: For my project at Leslie Lohman, I researched the arc of queer history over the last thirty to fifty years – roughly since Stonewall. I looked at images from the SALGA (South Asian Lesbian and Gay Association) archives in New York. Many of us have marched with SALGA during Pride, as one of the few nodes for queer identified or questioning people of South Asian origin. In looking at that archive, I actually found myself in a photo from 1994 or 1996. These poetic moments in the archive, moments that are both playful and political, attuned me to how our shared queer history inhabits play. Understanding the past gives us a way to move forward. We do not have to reinvent the wheel. We have always been here and so, what different forms of power structures were we in when we were here before? Thinking about representations of brown queerness, the relationship between play and archive shows up in my work and in my findings. I think of images of William Dorsey Swann from 1859, the first known documented black drag queen. Once freed from being an enslaved subject, he started to perform. But even as queerness and LGBT issues are occupying more space in mainstream cultural and media representations now, I think of my personal relationship to play, which often came from speculating or imagining myself inhabiting spaces that I wanted to experience but had never been in. Spaces like Paradise Garage, which was a very popular nightclub in New York. Giving house music to its audiences, there was depth and texture to its demographics. In other words, as a young queer person, this sense of play came up in how I inhabited other kinds of narratives and texts, such as Bollywood songs, pop music lyrics, fantasy stories, Archie comics, Scooby Doo. Whatever it was, I tried to locate a resonant subject for myself, and I did this from a very young age. Finally, I wanted to have some fun and share this prime example of inhabiting play from 1950s Bollywood. Finding no reflection in mainstream American culture – because there was no representation at that time or very little – this song, music video, and drag performance epitomizes play, that is, inhabiting other narratives by metaphor to expand the possibility of what could be:

(“Kajra Mohabbat Wala” from the 1955 film, Kismet)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kItK3kQlyko

NB: I think my queer brown heart just skipped a beat right back to a time I never inhabited but to an enactment of play I feel so interpellated by! I especially value encountering play as an archival method of yours that speaks to emergence. And, this working definition of “inhabiting other narratives by metaphor to expand the possibility of what could be” is very generative for me. Let’s turn to your current show at Leslie Lohman Museum. I love the femme-powered poetry of your title, A City Will Share Her Secrets If You Know How To Ask – can you say more about its inception? And if you can walk us through the work as a whole while zooming in on individual windows that would be great.

CG: The title was in part related to the lockdown when things went quiet, dark, and radio silent. There wasn’t a lot of information but there was the feeling that economic crisis was about to be widespread. This reminded me of the New York I grew up in where places were abandoned. There were many more instances of suffering – mental health issues visible on the streets and more homelessness too. The pandemic reveals inequities that already exist. In a way, the title refers to new ways I learned about and experienced the city, both because of how the pandemic impacted it, and in my research for the work.

The installation is located on the corner of Wooster and Grand in Soho. Its point of entry is an imagined space. I was thinking about the journey in the Divine Comedy: Inferno – not only for of the different cycles of hell that we have experienced in 2020 and the last 4 years being our very own spiral of hell, but also its narrative structure– the main character Dante enters the space with a Virgil, his teacher and guide (and this recurs in Sultana’s Dream with Sultana and sister Sarah). Given how the work extends across ten windows, I imagine this utopic imaginary to be capacious enough to hold dissent, conflict, and celebration together. To be clear, this isn’t a “it gets better” narrative because that is not the case and many people have been trying to dismantle this narrative for a while. The work alternates between these larger, more populated compositions on the one hand, to vignettes that are more fantastical and solitary, but still archivally rooted. The installation ends with a spatially and temporally layered city space that, alongside historical references to architecture, marks a kind of queer time through iconic images. For instance, I include a kiss in the clouds that is based on a poster and a bus campaign by Grand Fury. I remember logging this image as one of my first encounters seeing two people of color, possibly female-bodied, kissing. And while now such representation is expected or commonplace, at that time they were often met with vandalism. This is the confrontation they provoked.

Contemplating my own experience vis-à-vis these events and marches I’ve attended, so much has changed – and yet not. I came back to quite a bit this year. In 2020, when I went to the Trans Lives for Justice March on June 10th at the Brooklyn Museum, there was a massive crowd. By contrast, the first Trans March, which in 2005, was a small group of community marching from Union Square to the Piers. Thinking about the city and this vacillation between being in overwhelming public space and then in isolation, rhyming some of these images and moments felt important.

In A city will share her secrets if you know how to ask, figures are layered and grouped in different ways across the span of the work. One such group includes trans and gender non-conforming people who had been murdered in 2000, starting from January 1st up to when my work went to print. My work asks (and shows), what are the shadow narratives, the shadow city, that is, the parallel stories that aren’t being told? I also included images of trans elders and activists such as Lorena Borjas, who is standing next to the scales of justice. She was an activist in Queens who provided resources, shelter, and refuge, to her community. On the road chanting to the crowds you see Sylvia Rivera, you see Marsha P. Johnsonon a poster, Grace Lee Boggs, Carmen Vasquez, June Chan, RBG and many more in the crowds; clusters of all who inspire me to envision the broader scope of coalition building and the history of social movements. You see DJ Rekha and Sunil Gupta, both of whom are artists, comrades, visionaries, and part of what grew me up. There’s many friends, colleagues, and other characters in history like Anna May Wong, the silent film actress, and Mona Foot who recently passed away of COVID19, who was another queer person very much cherished in the community.

My research on architectural history, from Lenape dwellings to the relatively recent unearthing of African burial grounds is also a big part of the work but for the purposes of time, I’ll stop here.

NB: Now I am curious about these architectural histories! What a rich archive that you cite, overlap, and engender. The way you connect across different notions of crowds, of spatial arrangements, and narrative devices like this extradiegetic character – a recurring element in your practice actually – ushers in a ‘brown commons,’ in the words of the great late José Muñoz. Indeed, this sense toward collectivity in difference has been so central to your work. For my last question to you, I’d like to return to the public dimensions of display. You’ve already shared so much about public display, but I’d like to dwell here some more especially given our particularly punctuated moment. I am curious about your intentions in public display and the effects of such display. Here I'm thinking of recent and older work installed at bus stops as well as your work up at Times Square.

CG: I made Urgency this year and the invitation by the Public Art Fund was particularly meaningful at a time when access museums and galleries was extremely difficult, whether because spaces are closed, or for health and safety issues, and obviously not at all during lockdown. Urgency was inspired by the idea of collective archetypes and a collective consciousness. I thought, if 2020 were to exist as an archetype, it would be urgency. The work was displayed on bus shelters around the city in ten to fifteen locations, maybe more. Fifty artists participated in this project, and so it was quite sprawling and dynamic. As someone who spent a lot of time waiting for the subway or on the bus, that time in transit, in movement, the time spent waiting, as both liminal and ritual, is really important. And it’s amazing to have art engage you during that ‘in between’ time. Like a piece of music, one can encounter the same works public art multiple times over the course of months, maybe years. Maybe you see something differently depending on your mood, your day, what you read in the news, etc. This opportunity for a repeated encounter, that could be very casual, in the end accrues, suffusing the experience and overall meaning of the piece--as in listening to an album over and over.

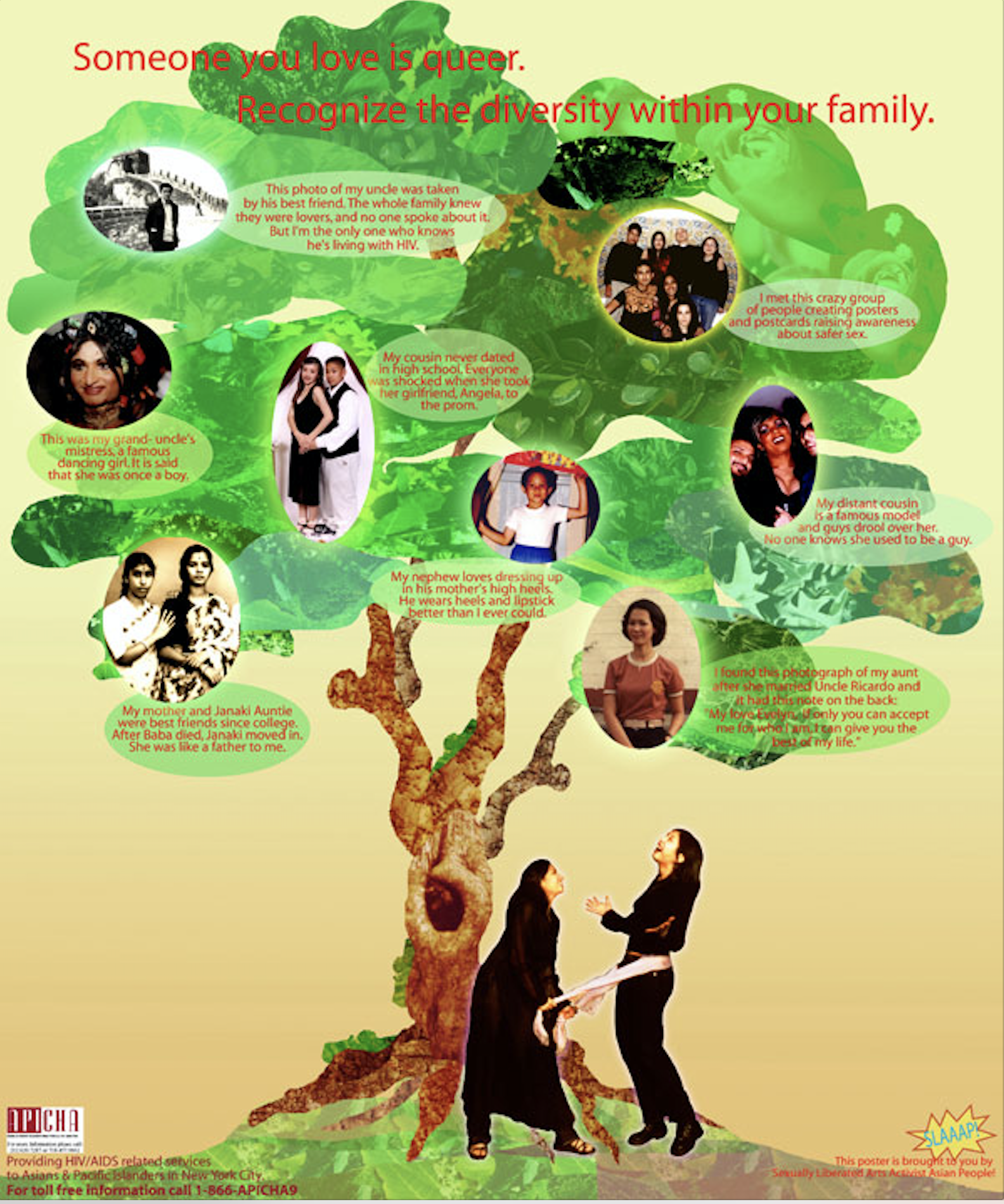

One of the first public art pieces I made was with SLAAAP! (Sexually Liberated Asian Artist Activist People!), a queer media art activist group active from roughly 1997-2002. In 2000-2001, in a project supported by the Queens Museum of Art and the Department of Health, we installed posters inside bus shelters of an alternative queer family tree, comprised of photos of friends and relatives community members contributed, accompanied by short texts that reflected the image and added speculative details. SLAAAP!’s work included postcard projects included wheatpasting posters around the city. These would live in the same visual zone of advertisements and concert posters. The playful images connected the visual pleasure of the images to start conversations and share important information and resources on issues such as immigration, xenophobia, sexuality, health, HIV status and safer sex.

To conclude, I’ll move from the analog billboard back to the animations inhabiting the space of digital billboard. Recently, I adapted the animations from the Rubin Museum, the ones we initially discussed, for a program in Times Square. The Times Square Art Alliance, which supports artists working in multiple media, takes over advertisement billboards in Times Square for four minutes at midnight every night for a month in a program called The Midnight Moment (though right now they have everything online). This is a great place to end because we’ve come full circle.

NB: I certainly can’t help but appreciate culminating so elliptically given the contents of our conversation. Whilst creating new, urgent iconography, I am attentive to your returns here to time, motion, and to the influences of the street, both its public and aesthetic dimensions. Thank you so much Chitra for everything – for your time, and for the occasion to think alongside you and your work.

Spotlight on Chitra Ganesh is organized in collaboration with curator Aziz Sohail.

further coverage on Chitra ganesh

Essays by Dr. Natasha Bissonauth on queer artists in the South Asian Diaspora

Dr. Bissonauth’s article in Art Journal tracks the reception of Sunil Gupta’s photos in Paris and New Delhi, and how queer racialized desire undergirds orientalist and queer art histories.

In “The Future of Museological Display: Chitra Ganesh’s Speculative Encounters,” Dr. Bissonauth argues that the artist's science fictional aesthetic conjures the possibility of temporarily taking over spaces of permanent display; because there is impact in ephemeral gestures.

Dr. Bissonauth’s article in South Asia journal on Sa’dia Rehman is set in the Queens Museum bathroom for the show Fatal Love (2005). She approaches the scatological humor of her installation, Lotah Stories, as a processing and consequent subversion of immigrant shame.