Annu Palakunnathu Matthew

Carving out space for historically under-represented narratives for people of color.

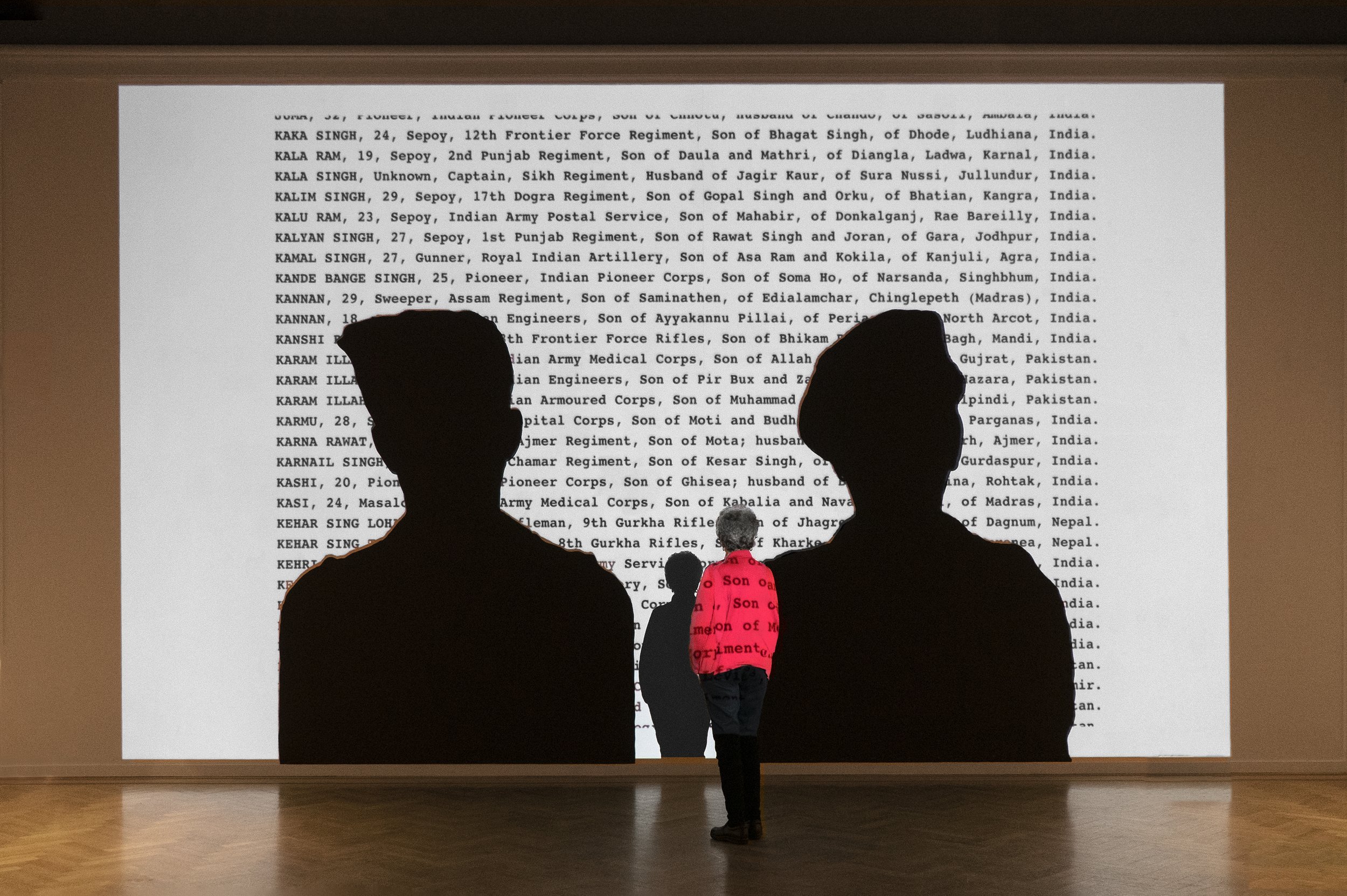

Annu Matthew explores hidden histories, untold stories, and traumatic communal experiences through her perspective as a person who self-identifies as 'transcultural’ - a global citizen who has been a resident of three continents. Using existing photographic material and archives that are personal, historical, and communal, Matthew raises socio/political questions through known imagery to prompt audiences to rethink their notions and assumptions.

The artist’s photo-based practice is a striking blend of still and moving imagery that draws on archival photographs as a source of inspiration to re-examine historical narratives and colonization's legacies. By employing various digital techniques and sculpture in her new media installations, Mathew encourages a re-viewing and re-narrativization of the past.

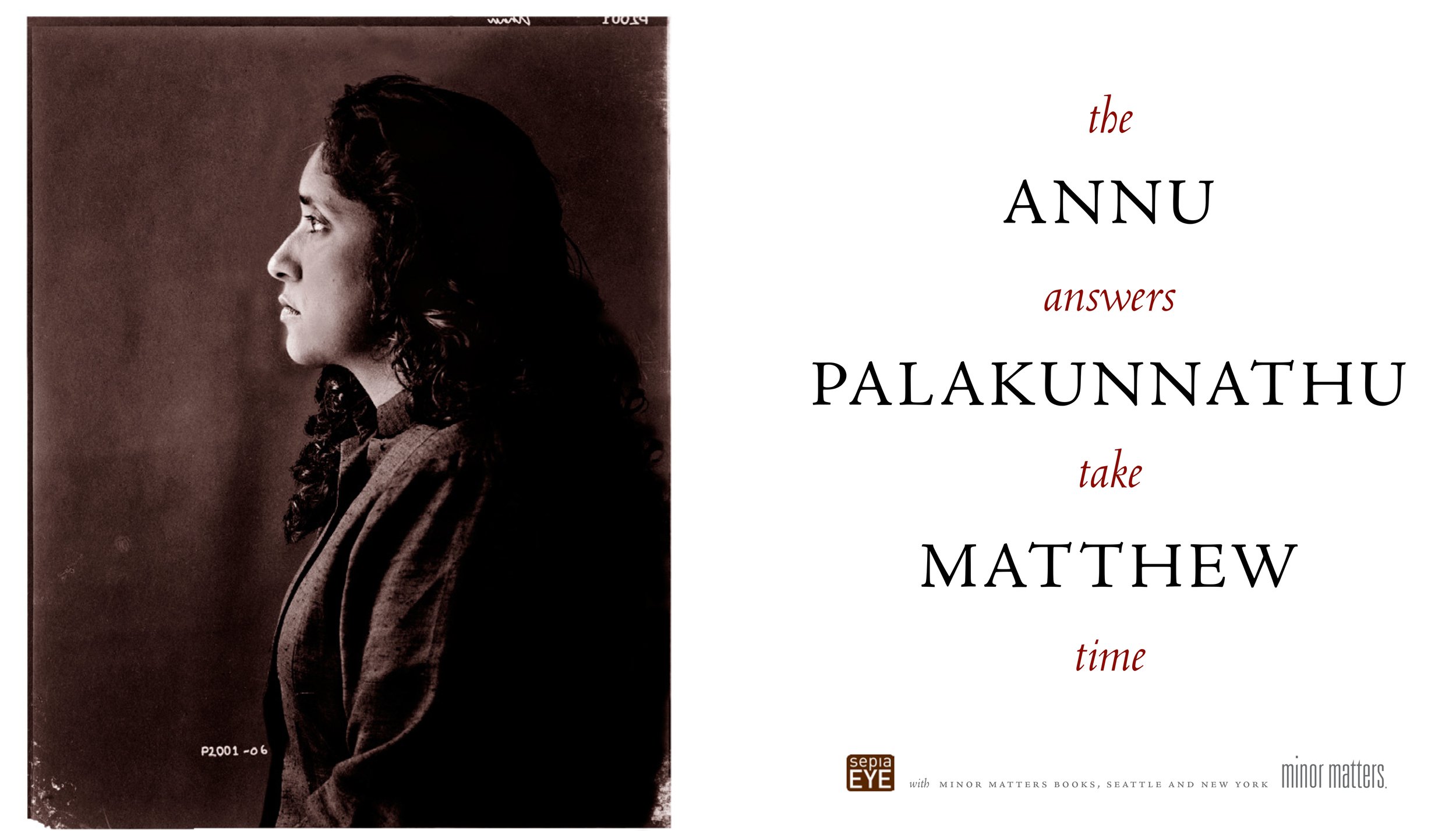

Matthew is a Professor of Art at the University of Rhode Island and was the Director of the Center for the Humanities from 2013-2019, and the 2015-17 Silvia-Chandley Professor of Nonviolence and Peace Studies and is represented by sepiaEYE, New York City. Her monograph from Minor Matters Books will be published this Fall (2022.)

““The mostly album-size photographs in this compact but far-ranging gallery survey are about the intensities and confusions of a cultural mixing that makes the artist, psychologically, both a global citizen and an outsider, at home and in transit, wherever she is. And it’s about photography as document and fiction: souvenir, re-enactment and imaginative projection. ””

Having lived between cultures, you describe yourself as transcultural. Can you talk to us about how you have navigated these multiple identities in your work and how it has shaped its trajectory over the years?

The experience of living between England, India, and the United States allows me to have both an insider and an outsider perspective. My transcultural experience is of belonging to none yet belonging to all three. This experience prompted me to collaborate with my subjects to tell their deeply personal stories to evoke empathy from an audience outside those communities.

Some of this perspective is reflected very early on in Memories of India, which are black and white photographs of my cultural homeland. The small precious photos reflect my knowledge and understanding of the culture and reminisce India's sights, sounds, and gestures. Yet they contain no faces or narrative. An Indian from India explores the confusion between my type of Indian and the Indigenous in the United States of America. This work started because of my amalgamation of accents which meant people couldn't place "where I was really from." The Virtual Immigrant explores a similar subliminal space of living between cultures. The work visualizes how the virtual immigrant flip flops between working as an American call center worker at night while in India to going home in the morning to become the son/daughter of an Indian family with all its comforts and constraints.

Your work deals with malleability, identity and memory, and the way the past informs the present. Was there one defining moment or perhaps an experience that prompted you to create your first body of work and engage with these themes?

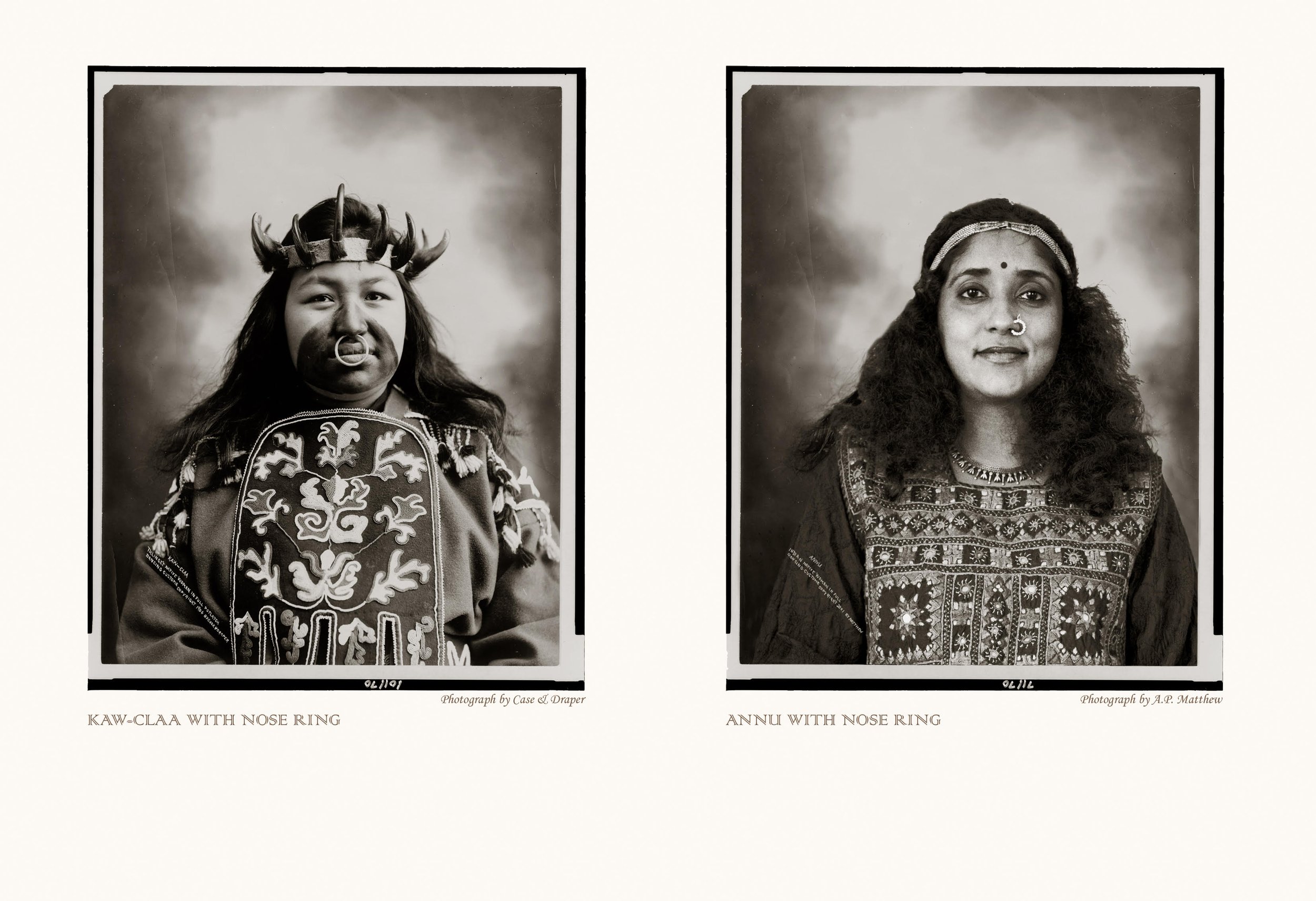

Being consistently asked, "where are you really from" reinforces my experience of being the "other." If I say that I am an Indian, I often have to clarify that I am an Indian from India. Christopher Columbus started this confusion when he thought he had found the Indies (a historical term) and called the native people of America collectively Indians. The more I researched for this project, I also learned about the history of the Indigenous, especially the strange similarities in the way they were represented in the history of photography. Like the Indians by the British.

This was the inspiration for An Indian from India, (below) which started my lifelong work related to the malleability of identity and memory.

'An Indian from India' is driven by your personal experience as an immigrant and is your artistic response to the question "Where are you really from?" Can you talk to us about how this collection of works comments on colonial history, race, and stereotypes?

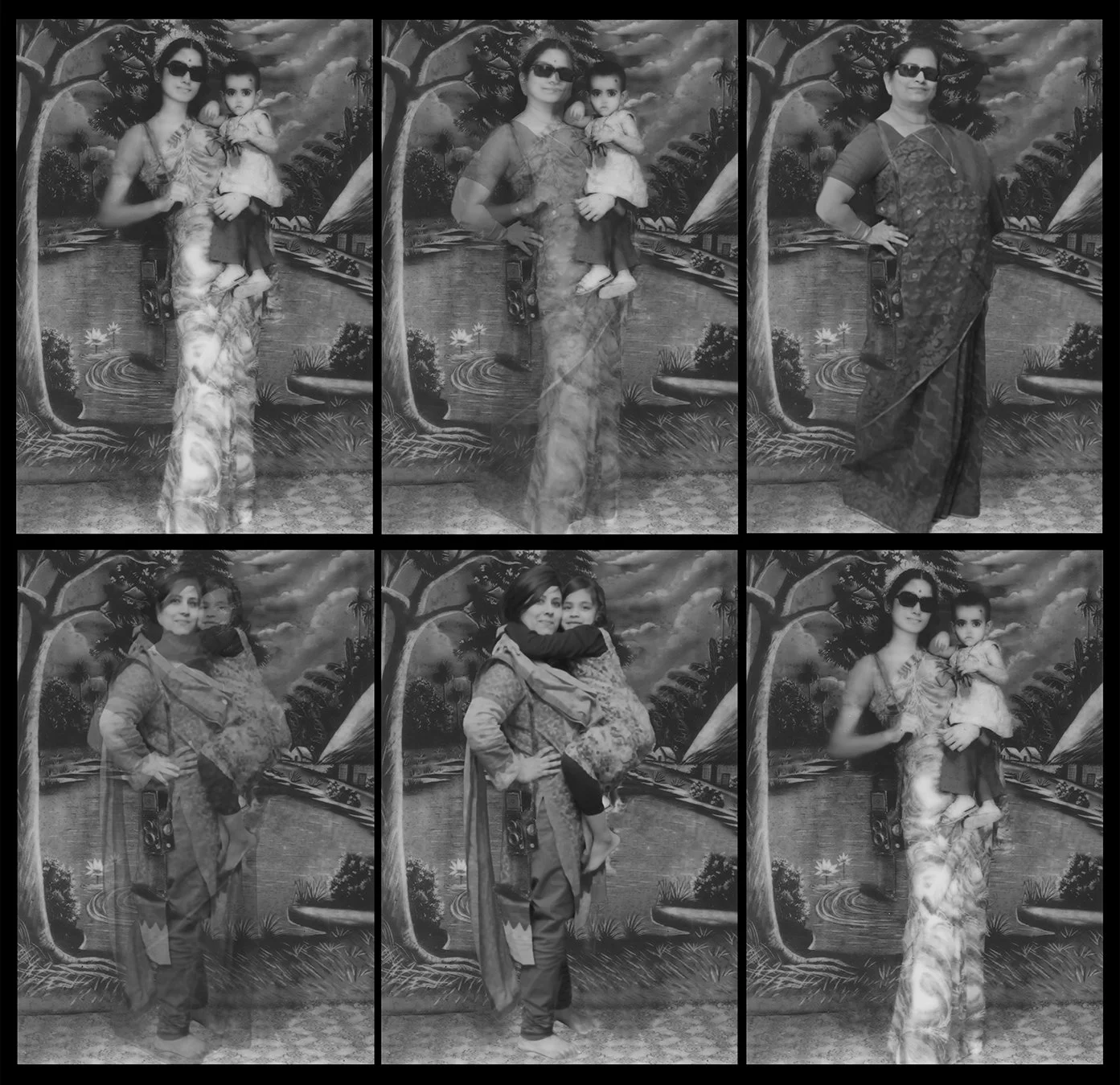

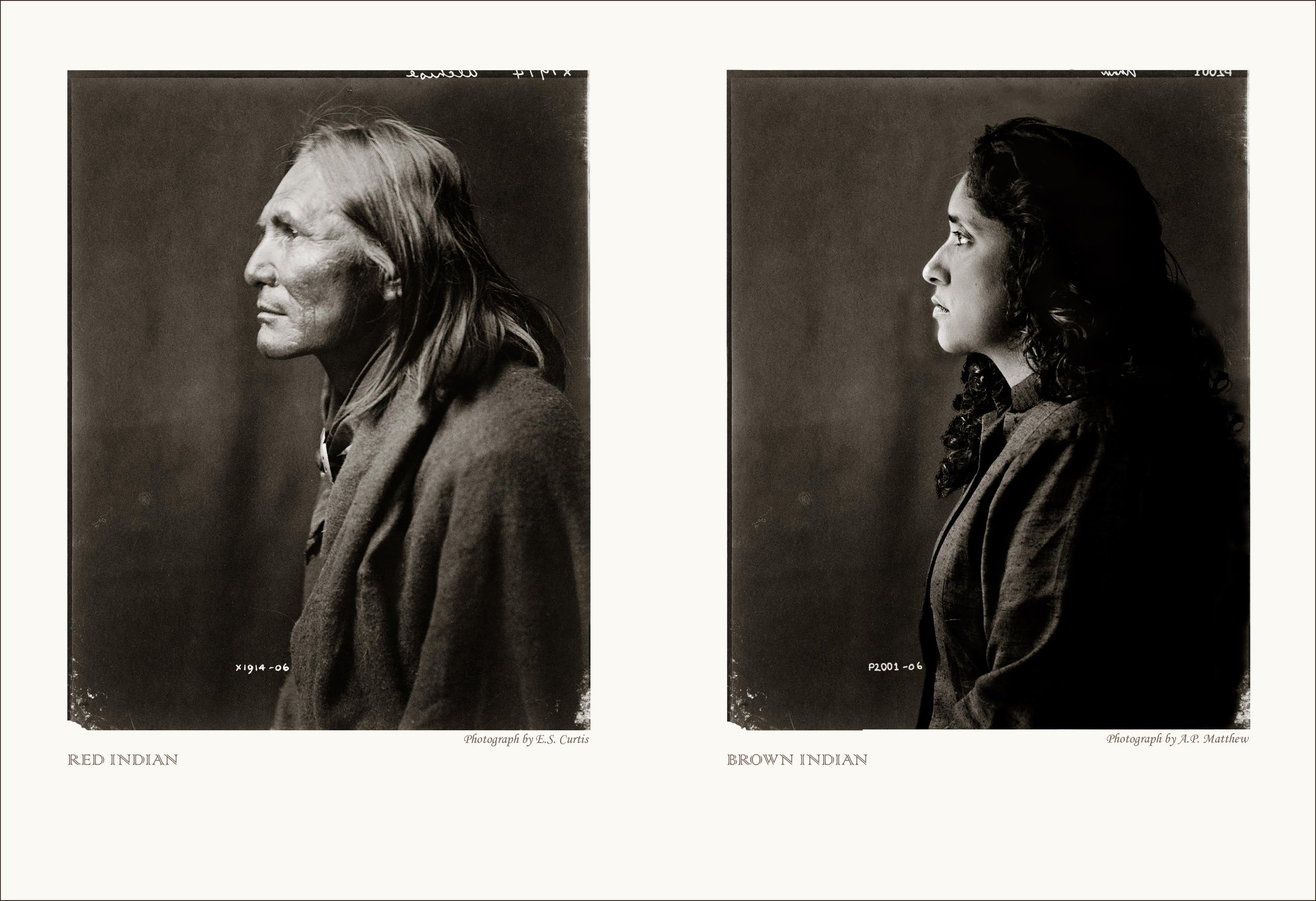

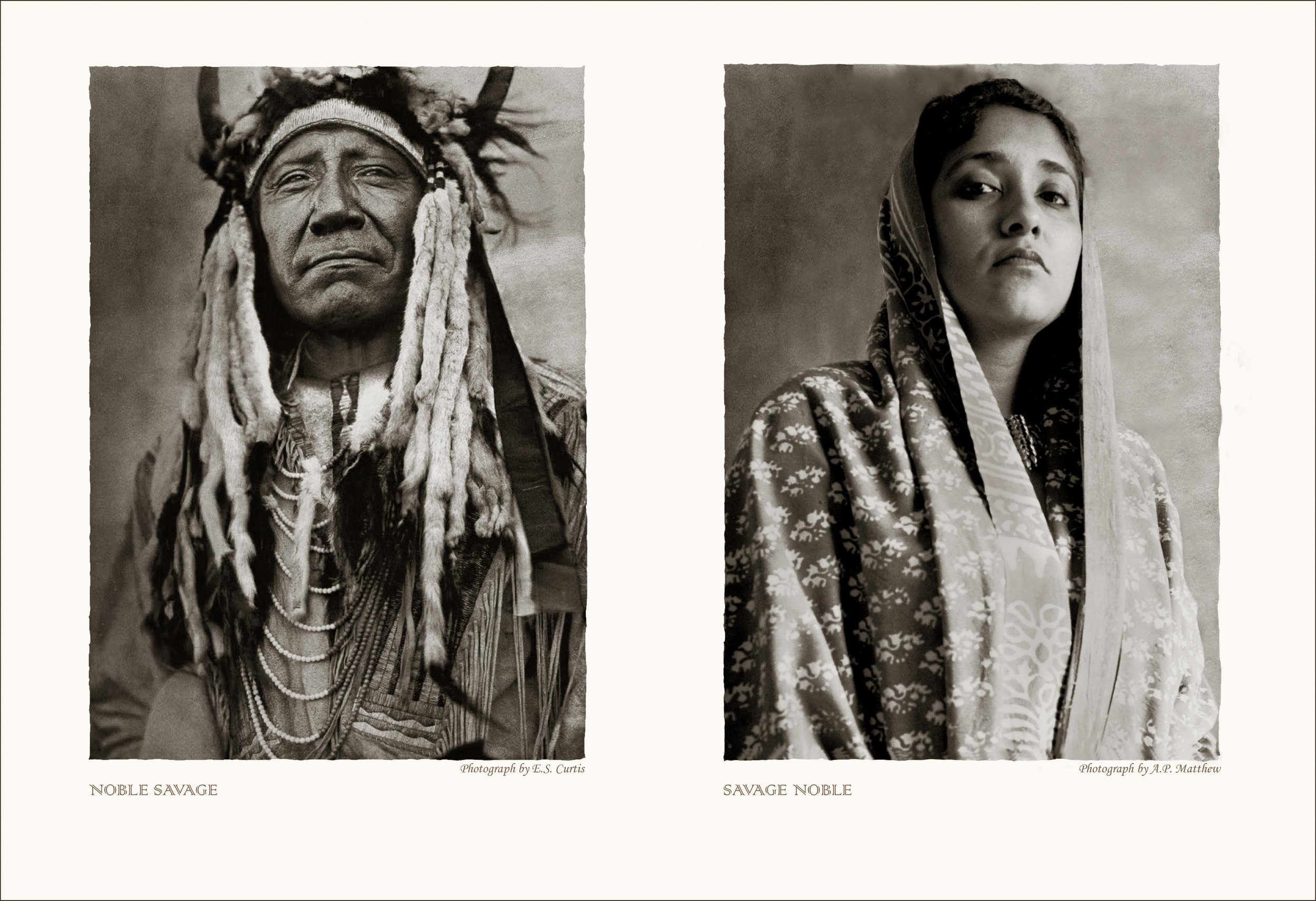

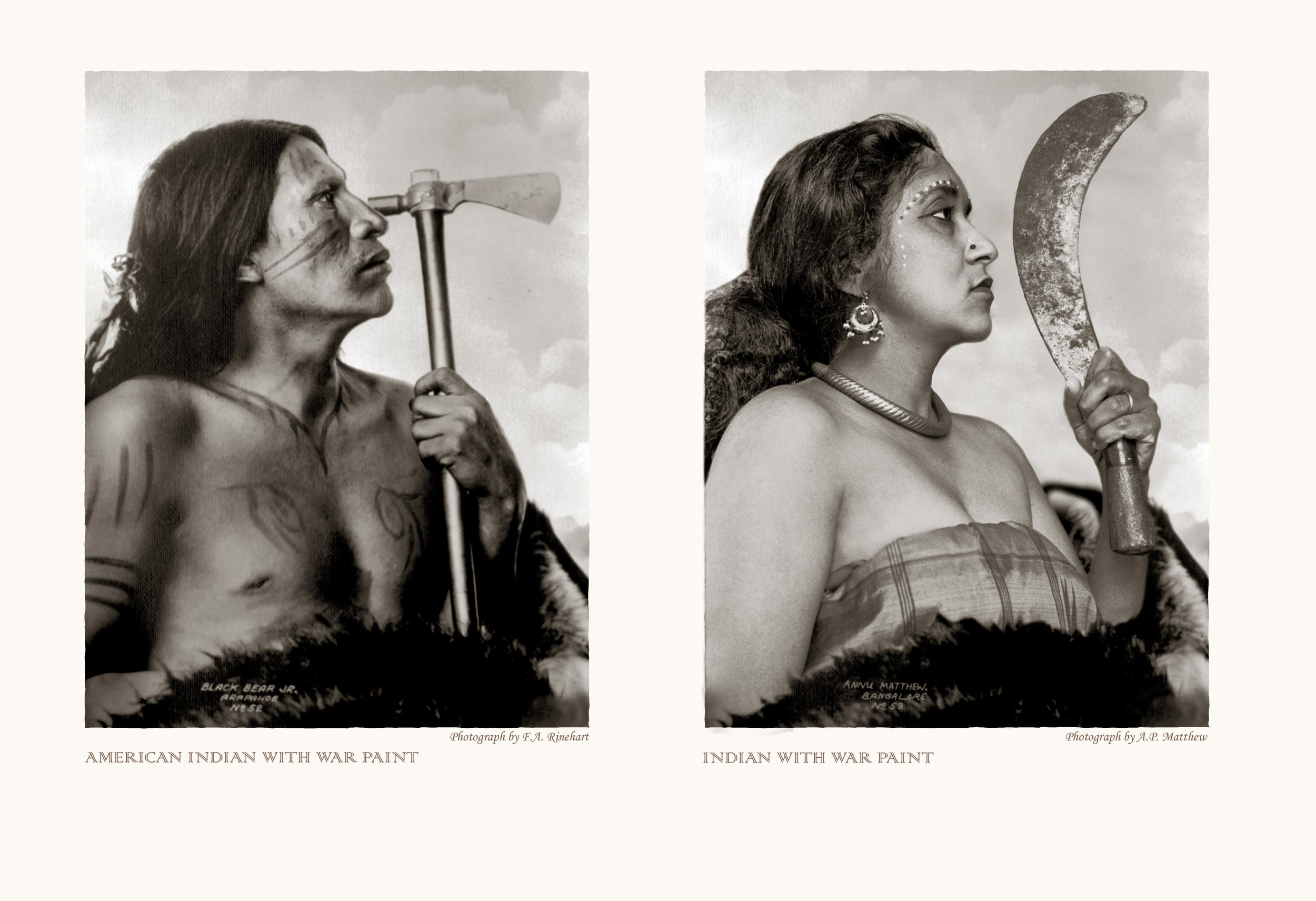

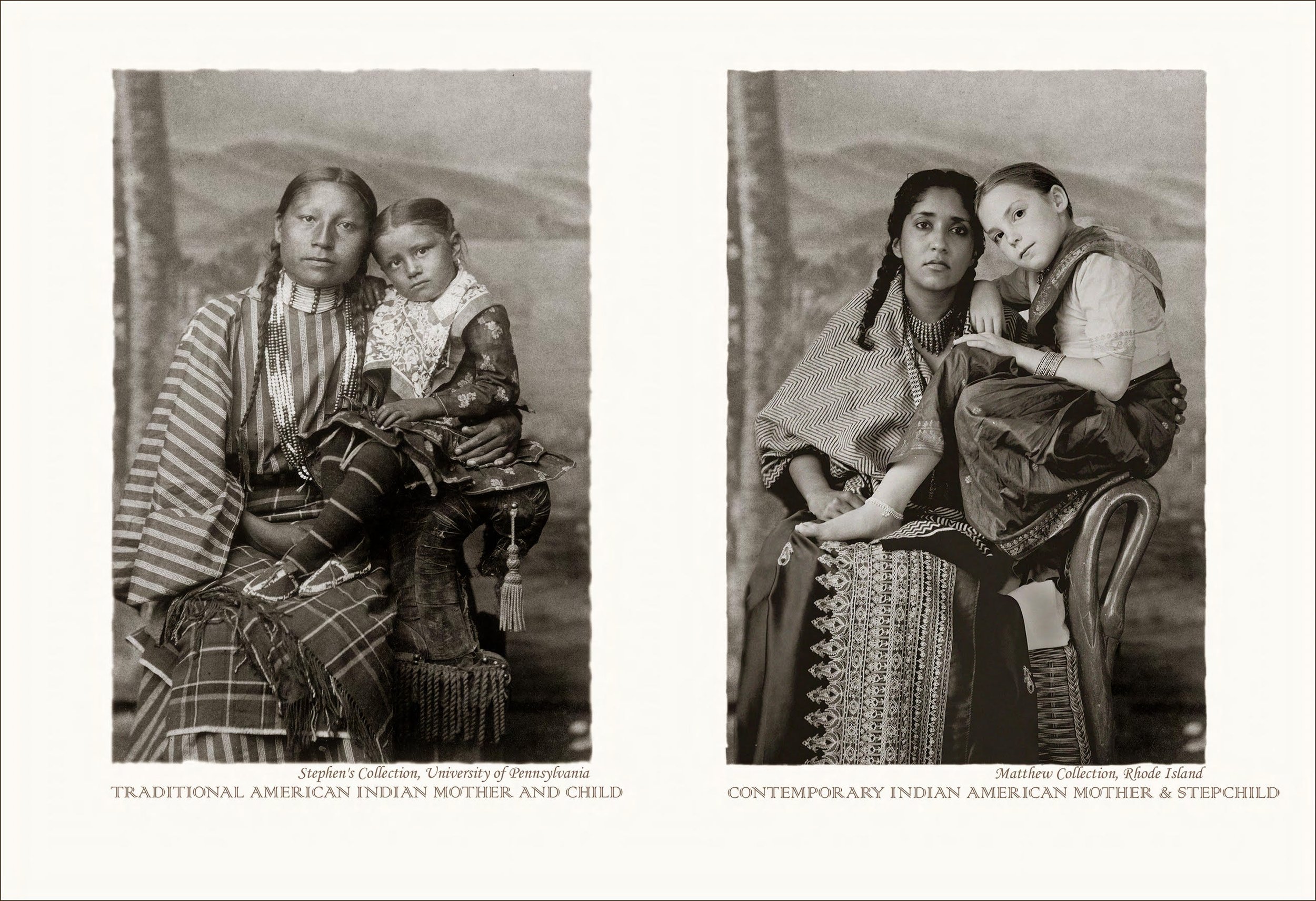

In the portfolio An Indian from India, I look at the other "Indian." I play on my perceived "otherness," using photographs of the Indigenous from the late Nineteenth and early Twentieth Century from archives like the Denver library and the Library of Congress. These archival photographs perpetuated stereotypes. I pair them with self-portraits that echo the original. My titles riff on historical titles and use humor to reverse the gaze to confront the colonial perspective. In the work, I find similarities in the widely disseminated nineteenth and twentieth-century photographs of Indigenous. They were portrayed as "the primitive natives," just like the colonial gaze of the Nineteenth century British photographers working in India. Susan Sontag and Roland Barthes referenced the unequal power structure between photographer and subject. It is reinforced when seeing the photographs created or "taken" by the British in Colonial India and categorized in the book "People of India." The objectification, stereotyping, categorizing, and exoticizing, combined with the lack of agency over how they will be represented, always made me uncomfortable as a South Asian woman. The impact of these questions on the An Indian from India is apparent as I turn the camera onto myself to question and challenge this power structure and the distorted legacy of the colonial gaze.

Who are your biggest influences and inspirations?

My influences and inspirations intersect across various spheres. They include the people I collaborate with, the joie de vivre of my 4-year-old friend, Benny, and my husband, David Helfer Wells, an influencer and critic! Other inspirations include my students who embrace the medium in new ways to techniques and software I discover through the expanding digital toolbox. Artists like Doris Salcedo and James Turrell have significantly influenced and inspired me.

Would you say that your artistic process has evolved in response to the photographic and archival material you engage with? From your medium to your ever-expanding toolbox, from personal histories to communal. Talk to us about your progression as a conceptual, installation-driven artist.

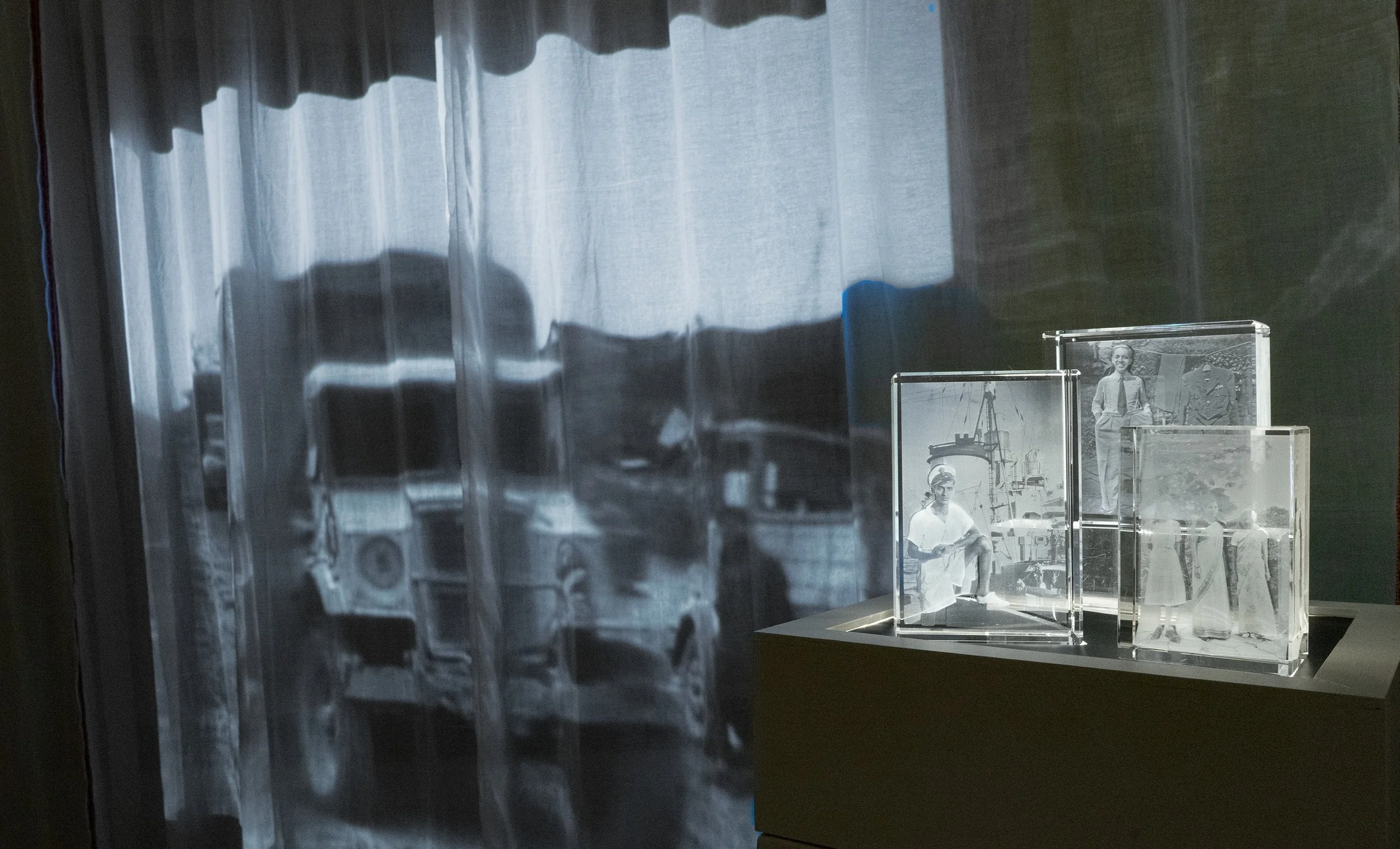

The progression of my work now looks logical, but the way it unfolded is very organic. I started as a traditional black and white film photographer who used a $20 Holga camera to create Memories of India. From that work, I evolved to creating diptychs in the more conceptual project mentioned above, An Indian from India. The work then moved to images moving back and forth using lenticular prints in The Virtual Immigrant (like the "winky" images you may have seen in cereal boxes.) Thanks to experimentation during the MacColl Johnson fellowship, I used family photographs morphing through generations via photo-animations in To Majority Minority (mentioned below.) My work has recently become sculptural, using hollowed-out books and 3D laser cut photos in crystals in installations.

I have always wanted my work to be accessible to larger audiences. So, a lot of my work uses familiar images as a starting point. From Edward Curtis's images of the Indigenous to family photos and more recently edited archival film footage of the Indian soldiers fighting in World War II.

Conceptually, my work started with my own immigrant experience. I have since expanded to collaborate with communities to give voice to their unknown and sometimes unacknowledged histories- As in Stories of Partition – India and Pakistan, The UNREMEMBERED – Indian soldiers of World War II.

Each project seems to have created a framework for the subsequent work. Can you speak to the generative nature of these works and how they have influenced your creative practice?

I have found that one project reveals new threads that lead to another. The ideas are often discovered through my research or conversations with the families I collaborate with. I then iterate versions with many failures until I settle on an approach where the concept and technique converge.

In the U.S. the month of May is dedicated to recognizing and celebrating the history and accomplishments of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders. 'To Majority Minority' contributes to this conversation in a very profound way by expanding what is considered to be American history.

Can you talk to us about this project and how you navigate the roles and identities of insider and outsider; these works?

Many of us don't look like the stereotypical "American" and have repeatedly been made aware that many think we don't belong. Recent examples include the internment of Japanese Americans after the attack on Pearl Harbor in World War II and the hate that those of us who looked Middle Eastern experienced after 9/11. The rising anti-immigrant rhetoric in contemporary politics has only increased over the last decade, including increasing anti-Asian attacks.

To Majority Minority asks questions beyond, "where are you really from?" to help others understand immigrants who don't look stereotypically "American" but are Americans. The irony is that by 2050, so-called "minority" populations in the U.S.A. will become the majority.

I explore immigration's personal stories in this project, starting with family photographs. I collaborate with multiple generations of the family to photograph them re-enacting the historical image and distilling down their resonant immigrant story. Old photos reignite memories and spark conversation, and, like a time machine, transport us back to the past. The old photos reflect where we have come, revealing family histories and shared stories of immigration. To Majority Minority spans time, national boundaries, and borders to visualize migration in a way that a single image cannot. The final animation weaves through time, allowing the viewer to simultaneously ponder America's immigrant past and these family's stories.

In the question, you ask how I navigate the roles and identities of an insider and an outsider. The families I interviewed were from different countries. So, as an immigrant to the U.S., we share that commonality. They allowed me into their homes and told me their stories even though I was an outsider to their culture of origin.

Minor Matter Books is publishing a mid-career survey of your work this Fall, a monograph titled - 'The Answers Take Time'. The books sequence is its own journey through geographies and time, influenced by the irrefutable narratives of population displacement, and the imperfection of memories.

What does this project mean to you and what's next? What are you currently working on?

I wish that the book was a done deal. It will only be published if 500 people sign up as co-publishers! I hope some of your readers will. I have 324 out of 500 backers and have under a month to achieve this goal.

The choices of the publisher, Minor Matters books, has drawn out interesting connections between my older and newer work to recontextualize it in exciting ways. This will allow the reader to dig deeper into the work, and the accompanying essays will give the work more context. I hope it will also help the reader appreciate the range of work and varied topics in my work, where the technique dovetails with the concept. The book lives beyond the timeframe of an exhibition. It helps people give context and gather a deeper understanding of the span of my work of 20 years.

What am I currently working on? I leave in June for Italy to meet and collaborate with the descendants of Italian families who sheltered escaping Indian Prisoners of War till the end of World War II. They did this at the risk of their own lives. It is such a positive, uplifting story, especially as we deal with the chaos, negativity, the aftermath of the pandemic, and the uncertain future of the war in Ukraine.

Annu Palakunnathu Matthew is a Professor of Art at the University of Rhode Island and was the Director of the Center for the Humanities from 2013-2019, and the 2015-17 Silvia-Chandley Professor of Nonviolence and Peace Studies and is represented by sepiaEYE, New York City.

Matthew's recent solo exhibitions include the Royal Ontario Museum, Canada, Nuit Blanche Toronto, Newport Art Museum, and sepiaEYE, NYC. Matthew has also exhibited her work at the RISD Museum, Newark Art Museum, MFA Boston, San Jose Museum of Art, Museum of Fine Arts (TX), Victoria & Albert Museum (London), 2018 Kochi-Muziris Biennale, 2018 Fotofest Biennial, 2009 Guangzhou Photo Biennial as well as at the Smithsonian.

Grants and fellowships that have supported her work include a MacColl Johnson, John Guttman, two Fulbright Fellowships, and grants from the Rhode Island State Council of the Arts. In addition, she has been an artist in residence at Civitella Ranieri, Lightwork, Yaddo, and MacDowell.

ALL IMAGES COURTESY THE ARTIST AND SEPIAEYE, NYC