Pritika Chowdhry

The artist’s anti-memorials create alternate ways to remember and memorialize traumatic geopolitical events, from the dual lenses of diasporic postmemory.

Tell us about yourself. How would you describe your art practice?

Sure, I guess I would say that I am a post-colonial, feminist artist. I make experiential art installations about traumatic geopolitical events such as the Partition of India and Pakistan, and 9/11. I think of my installations as anti-memorials that excavate the counter-memories of these events, from a postmemory perspective. By and large, my work spotlights experiences that are marginalized from the dominant discourse, and not memorialized in national monuments. I often get asked what these terms are, so it might be best to start there.

What is an anti-memorial?

James E Young describes an anti-memorial as, “Anti-memorials aim not to console but to provoke, not to remain fixed but to change, not to be everlasting but to disappear, not to be ignored by passers-by but to demand interaction, not to remain pristine but to invite their own violation and not to accept graciously the burden of memory but to drop it at the public’s feet.” So anti-memorials are in some ways opposite of public state-sponsored monuments.

What is counter-memory?

Michel Foucault coined the term, counter-memory to describe “a modality of history that opposes history as knowledge or history as truth.” For Foucault, counter-memory was an act of resistance in which one critically examines the history and excavates the narratives that have been subjugated.

What is postmemory?Marianne Hirsch defines postmemory as “the relationship that the generation after bears to the personal, collective, and cultural trauma of those who came before, to experiences they remember only by means of the stories, images, and behaviors among which they grew up. But these experiences were transmitted to them so deeply and affectively as to seem to constitute memories in their own right. Postmemory´s connection to the past is thus actually mediated not by recall but by imaginative investment, projection, and creation.”

Your research investigates The Partition of British India, that created Pakistan in 1947 and Bangladesh in 1971. Tell us how it all began.

I was born and brought up in India, and I was there till I turned 26. My most impressionable and formative years were spent in the India of the 1980s and 90s. Those were the decades of liberalization and a rising Hindu Right. The demolition of the Babri Mosque in 1992 and the riots thereafter left a deep impression on me. I was slowly understanding that the idea of India as a secular country was shaky, at best.

In 2002, when the Gujarat Pogrom happened, I realized how far India had moved from its secular ideals. That was the time when I started asking my parents about 1947. My mother is Sindhi her family is from Karachi. Her father was in the railways and their whole extended family moved from Karachi to Delhi in August 1947, at the height of the communal riots. My father’s family was in Kolkata at that time, and while they did not have to migrate, they witnessed communal violence in West Bengal.

How do you account for the fact that although you have not been a first-hand witness to many of the incidents that form the basis of your works, they have impacted you enough to be manifested in your work?

As a grandchild of the Partition, I am a secondary witness and have been influenced by various retellings of the history of the Partition and the Partition riots. Operating from this location of postmemory, I have absorbed my family’s experiences of the Partition from the East and West sides. Growing up in India, I saw firsthand how the Indian government appropriates the history of the Partition and uses the Partition violence to perpetuate bias against Muslims. Narendra Modi, the prime minister of India known for his Hindu Right bias, making August 14, the founding day of Pakistan, as “Partition Horrors Remembrance Day” is an apt example of this sort of appropriation.

Paul Brass coined the phrase, ‘Institutionalized Riot System’ (IRS) to explain the dramatic production of riots on a regular basis in India, by the Hindu Right. As a Hindu, I felt that it was my responsibility to share this research about the religion-based politics in India in order to create bridges between Hindus and Muslims.

Your body of work largely consists of installations and sculptures. What drew you to these mediums?

That’s a great question! I drew and painted until Grad School and kept trying to make my paintings and drawings more three dimensional using chiaroscuro techniques. Then I happened to take a ceramics class in grad school and that really transformed my practice to being more sculptural. As I started to see how sculptures take up space, I moved into making installations to sculpt space, and then incorporated soundscapes to create an experiential environment for viewers. The malleability of clay, but also its weight and density led me to explore other materials such as fabric, paper, metal, glass and most recently, neon! It has been an organic and intuitive evolution.

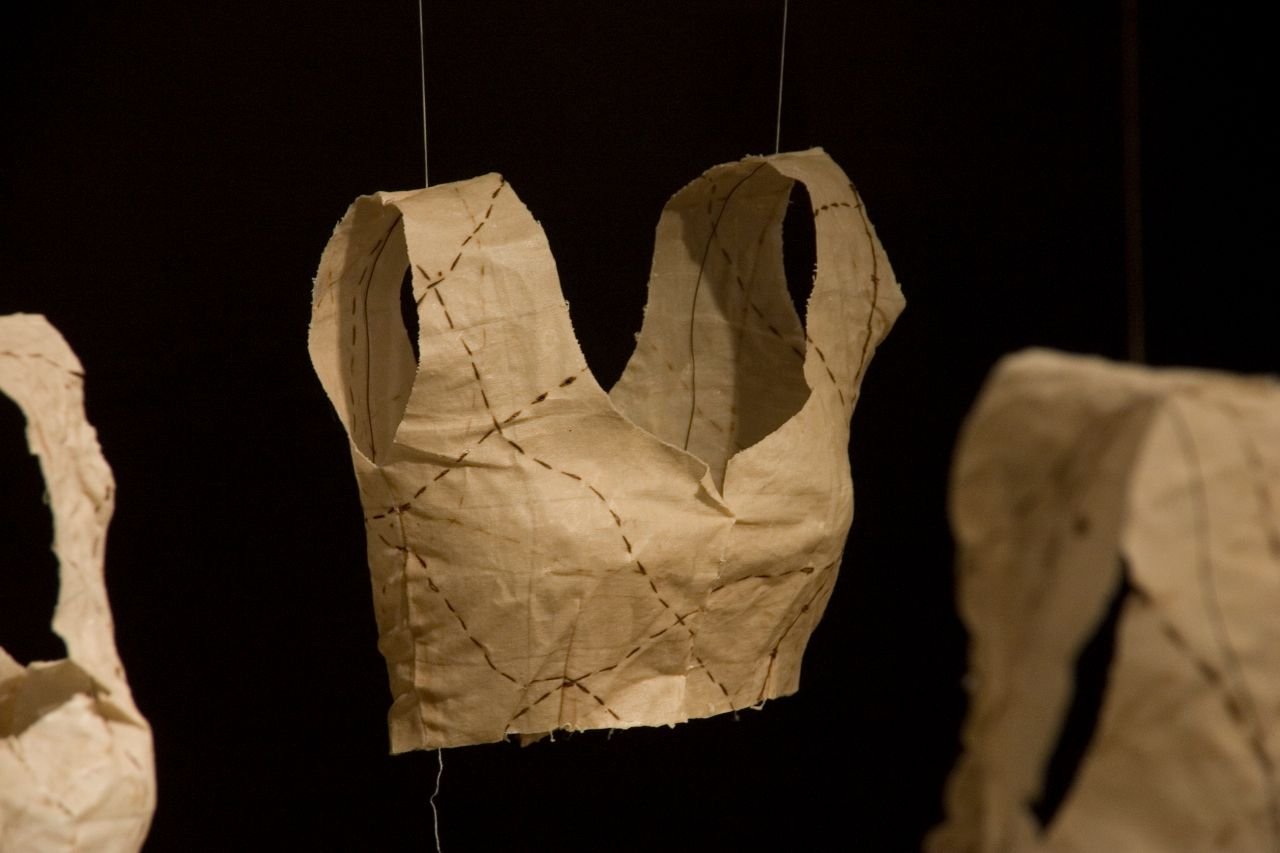

Sculptures, especially figurative sculptures, and more particularly, fragments of figurative sculptures, create ghostly twins of the human form. These figurative fragments in my work are a visceral embodiment of traumatic experiences and memories, that are difficult and uncomfortable to recall, memorialize, or talk about.

Your anti-memorials are temporary in nature. Walk us through some of your installations-

As an example, my installation, Archive of 1919 connects various events that happened in 1919—the Jallianwalla Bagh Massacre, which catalyzed India’s Independence movement and the, Irish War of Independence, the Versailles Treaty, the Third Anglo-Afghan War, May Fourth Revolution in Tianmen Square, and the Bloody Summer in Chicago, one of the worst race riots in America.

In reading Salman Rushdie’s Midnight Children, I was drawn to the spittoon, a vessel for expectorate as a carrier for memories. I used antique spittoons from the 1920s, which are relics of the early 20th century, as containers of memory, and hand- engraved maps, names of revolutions, declarations of independence, and treaties onto their exterior. By transforming the spittoon into a memorial rather than a vessel to hide waste, the work counters attempts to obscure the violence of colonialism, while recognizing how knowledge of historical atrocities has been subjugated. While these events are historicized as isolated events, I propose their interconnectedness; the Irish and Indian freedom fighters supported each other as they fought for independence from their British oppressors.

Below: Installation view of An Archive of 1919: The Year of the Great Crack-Up, at the Whittier Storefront gallery, in Minneapolis, MN

Broken Column is an ongoing site-specific, research-based art project that interrogates the role of public monuments in the formation of collective memory. The primary sites of memory are -

1. Jallianwallan Bagh memorial in Punjab, India

2. Minar-e-Pakistan monument, in Lahore, Pakistan

3. Martyred Intellectuals monument in Rayer Bazar, Dhaka, Bangladesh

The installation functions as an anti-memorial to the Partition of India in 1947, and the Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971. It triangulates public monuments in India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh through the counter-memories of these traumatic geopolitical events, through artistic interventions, and juxtaposes the counter-memories of these sites as a memory triad.

These sites of memory or lieux de memoire in Pierre Nora’s words are rich with collective memories of the Partitions of 1947 and 1971. In addition, certain historical objects from these countries have also been included in this project as objects of memory.

Below: Video Broken Column- Lahore Edition

““Pritika Chowdhry’s artwork is a powder keg of emotionality, raw talent, and visceral grit! I have never met a more thoughtful, theoretically engaged artist-scholar-educator-activist. Counter-Memory Project is the stuff of truth-telling, trauma-healing, and narrative-forging!”

”

What is the reason you chose to engage with the socio-political issues in your home country in your art?

I make work about the geopolitics of South Asia but I also make transnational connections in my work with the events in other countries. For example, I have been making anti-memorials to the Partition of India and Pakistan since 2007. But in several of Partition anti-memorials, I include partitions that have happened in other countries, such as Palestine, Ireland, Cyprus, Bosnia, Germany, Vietnam and Korea.

Similarly, in my anti-memorial to the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre, I included significant events that happened in 1919 around the world, such as the Treaty of Versailles, the Irish War of Independence, the Race Riots in the US, the War of Juarez in Mexico, the May Fourth Revolution in China, the Turkish War of Independence in Turkey, the Russian Civil War, the creation of the Weimar Republic in Germany, and several more.

In 2001, 9/11 happened and I experienced the overnight change in attitudes towards Muslims, Middle Easterners, and South Asians. This led to the creation of “Ghosts of 9/11: Ungrievable Lives,” in 2011, the 10th anniversary of 9/11, in which I commemorated the Muslim lives lost in Iraq and Afghanistan, and expanded it to include Syria, Yemen, and Pakistan, in 2021.

The themes in your works highlight generational social issues in South Asia, how can we in the United States bring about the type of radical change that is needed?

That’s a great question! We here in the US can do a lot. Firstly, educating the American and South Asian American publics about the geopolitics of South Asia from a historical and contemporary perspective will also enable a better understanding of the complex relationship US has with South Asia. This is even more important in a post-9/11 America where Islamophobia has increased and become more visible. Secondly, the South Asia diaspora has close links with families and friends back home, and is an important source of funds for all kinds of causes in our home countries. By engaging them in a non-partisan dialog about historical misrepresentations, we will be able to create long-term change in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh.

What is the next anti-memorial you are working on?

I have been working on creating a new set of neon sculptures and large-scale drawings that depict the Radcliffe Line, and the Lines of Control in Kashmir.

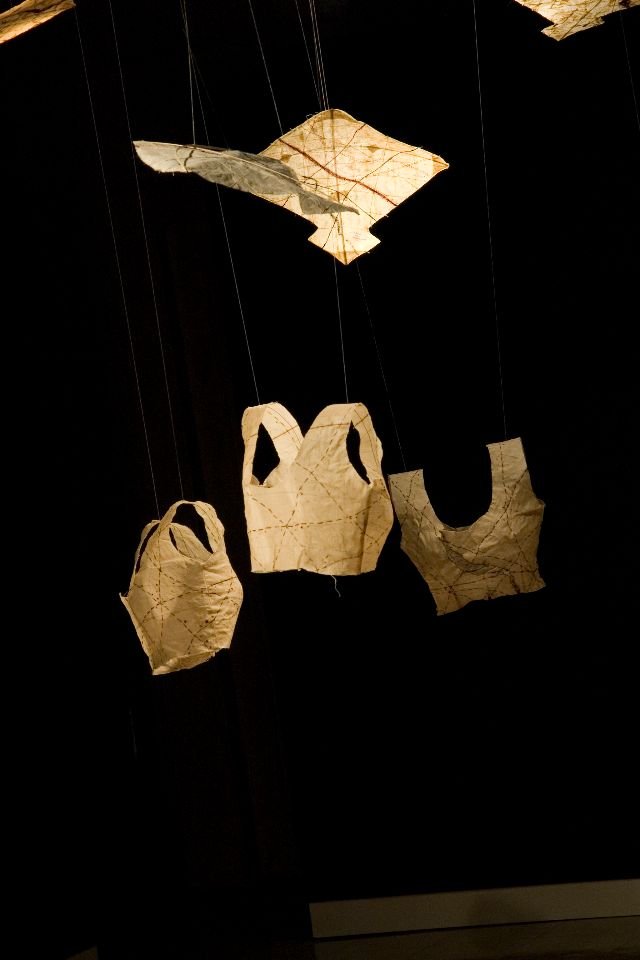

I will be debuting these new works in my upcoming solo exhibition at SAI, Unbearable Memories, Unspeakable Histories which addresses the Partition of India through art installations that serve to educate and evoke empathetic responses in viewers. Evoking corporeal bodies through a myriad of materials, the exhibition highlights generational resilience and resistance.

Pritika Chowdhry is a feminist and postcolonial artist, curator, and writer whose work is in both public and private collections.

Chowdhry has exhibited nationally and internationally in group and solo exhibitions in the Weisman Art Museum, Queens Museum, Hunterdon Museum, Islip Art Museum, Visual Arts Center of New Jersey, DoVA Temporary, Brodsky Center, and Cambridge Art Gallery.

Her work has been written up in various scholarly publications, including the journals GeoHumanities, Social Transformations Journal of the Global South, and Progress in Human Geography, in addition to news outlets such as CBS, NBC, and Hindustan Times.

She is the recipient of Vilas International Travel Fellowship, Edith and Sinaiko Frank Fellowship for a Woman in the Arts, Wisconsin Arts Board grant, and Minnesota State Arts Board grant.

She has presented her studio research projects at various national conferences, such as International Arts Symposium at NYU, The Contested Terrains of Globalization at UC-Irvine, and the South Asian Conference at UW-Madison.

Chowdhry holds an MFA in Studio Art and an MA in Visual Culture and Gender Studies from UW-Madison and has taught at Macalester College and the College of Visual Arts. Born and raised in India, Chowdhry is currently based in Chicago, IL.

ALL MEDIA COURTESY THE ARTIST